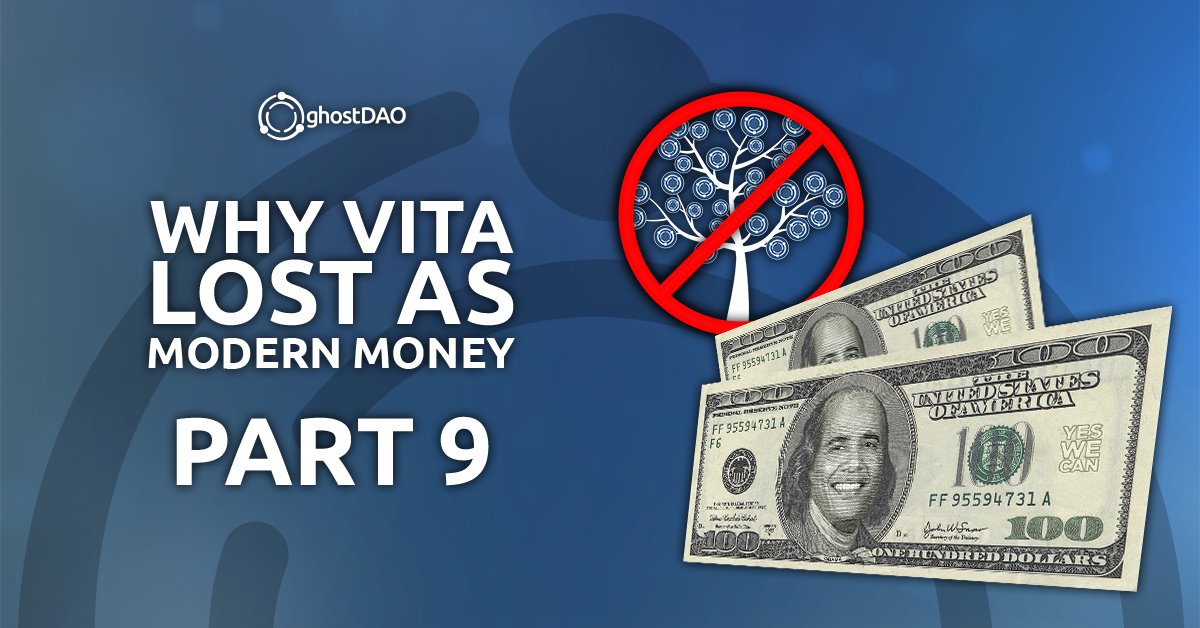

Vita vs. Reserve and Fiat

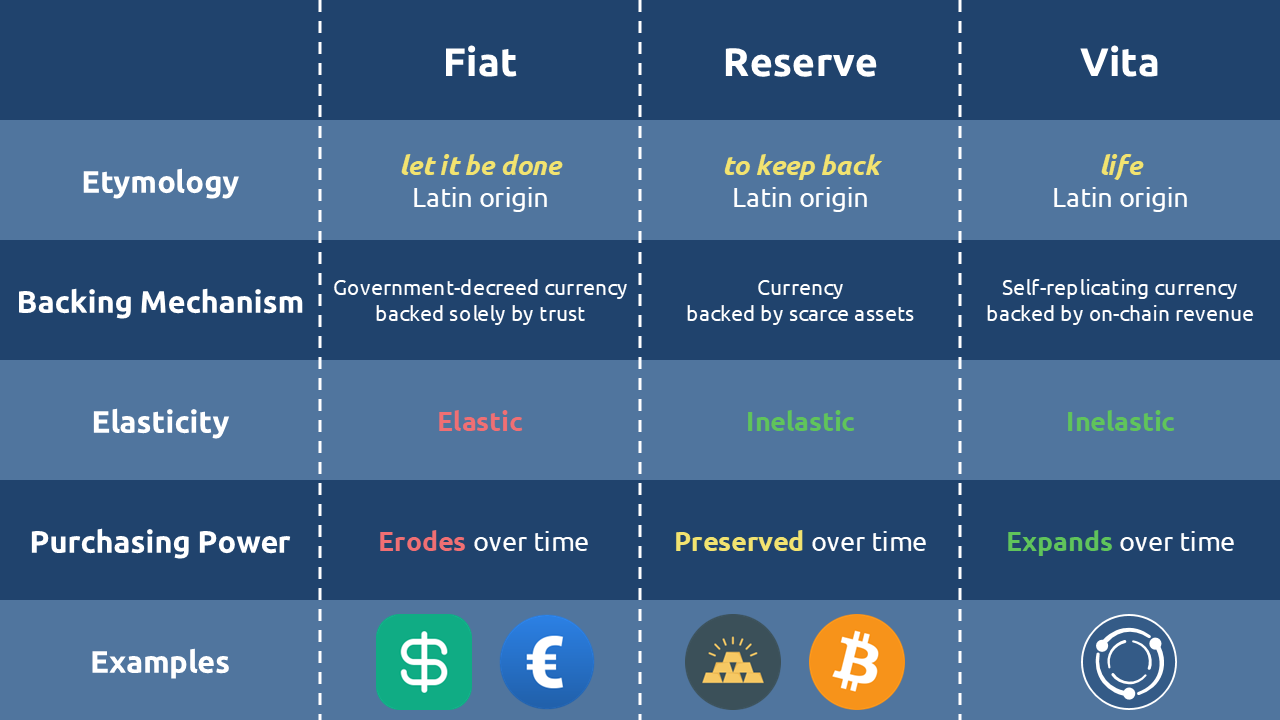

Previous analysis established that Vita possesses two compelling properties – inelasticity and self-replication – which appear to make it an ideal candidate for global money. Its inelastic supply ensures scarcity, while its capacity for self-replication not only preserves purchasing power (a trait shared with Reserve currencies) but actively expands it. In contrast, fiat money, with its inherently elastic supply, inevitably erodes purchasing power over time, placing it at a distinct disadvantage next to Vita.

This presents a puzzling question: if Vita’s monetary properties are so superior, why is it absent from today’s dominant monetary systems?

This very paradox was echoed by Carl Menger, a foundational figure in Austrian Economics, in his work The Origins of Money (1892). He pondered how seemingly useless metal disks or their paper representations became the accepted norm for all economic exchange.

Menger writes: “It is obvious even to the most ordinary intelligence, that a commodity should be given up by its owner in exchange for another more useful to him. But that every economic unit in a nation should be ready to exchange his goods for little metal disks apparently useless as such, or for documents representing the latter, is a procedure so opposed to the ordinary course of things, that we cannot well wonder if even a distinguished thinker like Savigny finds it downright ‘mysterious.’”

To unravel this mystery, we must return to first principles. This essay will examine the core foundations of money: its essential functions and the properties a material must possess to serve them effectively.

Introduction

As this overview suggests, there is no single, universally accepted definition of money within academic circles. Its precise origins remain somewhat mysterious. Consequently, the current monetary landscape – dominated by fiat currencies and previously by the gold standard – is not the result of a deliberate, scientific design but rather a sequence of historical developments. Money, in its present forms, simply emerged through a process of evolution; this does not, however, validate it as the optimal or most efficient monetary system possible.

Despite significant advancements in science, technology, and economic theory, the discourse on money remains deeply rooted in the foundational works of classical thinkers. Modern economists consistently engage with the ideas of seminal authors such as Aristotle, John Locke, and William Stanley Jevons to frame their understanding.

It is particularly noteworthy that Jevons, in his influential work Money and the Mechanism of Exchange, dedicated considerable attention to documenting the historical existence and use of what we term Vita money.

Currency in Pastoral State

In the chapter “Currency in the Pastoral State,” Jevons describes how livestock, such as sheep and cattle, emerged as a primary form of valuable and negotiable property in early societies. These animals were not merely subsistence resources but functioned as a key medium for storing and exchanging value.

He observes: “They are easily transferrable, convey themselves about, and can be kept for many years, so that they readily perform some of the functions of money.”

This relative mobility and durability made them a practical, though imperfect, tool for facilitating trade and measuring wealth in pastoral economies.

Currency in Agricultural State

The chapter “Currency in the Agricultural State” examines the widespread use of cultivated plant products as common instruments of exchange. Jevons details how various staple crops fulfilled monetary roles across different societies, moving beyond animal-based Vita money to a more varied set of commodities.

He provides specific examples: “Corn has been the medium of exchange in remote parts of Europe from the time of the ancient Greeks to the present day. In Norway corn is even deposited in banks, and lent and borrowed. What wheat, barley, and oats are to Europe, such is maize in parts of Central America, especially Mexico, where it formerly circulated. In many of the countries surrounding the Mediterranean, olive oil is one of the commonest articles of produce and consumption; being, moreover, pretty uniform in quality, durable, and easily divisible, it has long served as currency in the Ionian Islands, Mytilene, some towns of Asia Minor, and elsewhere in the Levant.”

Despite this rich and well-documented history of vegetable-based Vita money serving local economies for centuries, these commodities were ultimately hindered from becoming mainstream monetary choices. They lacked certain critical functions and properties required for a universal money, limitations that became more pronounced as economies grew more complex and interconnected.

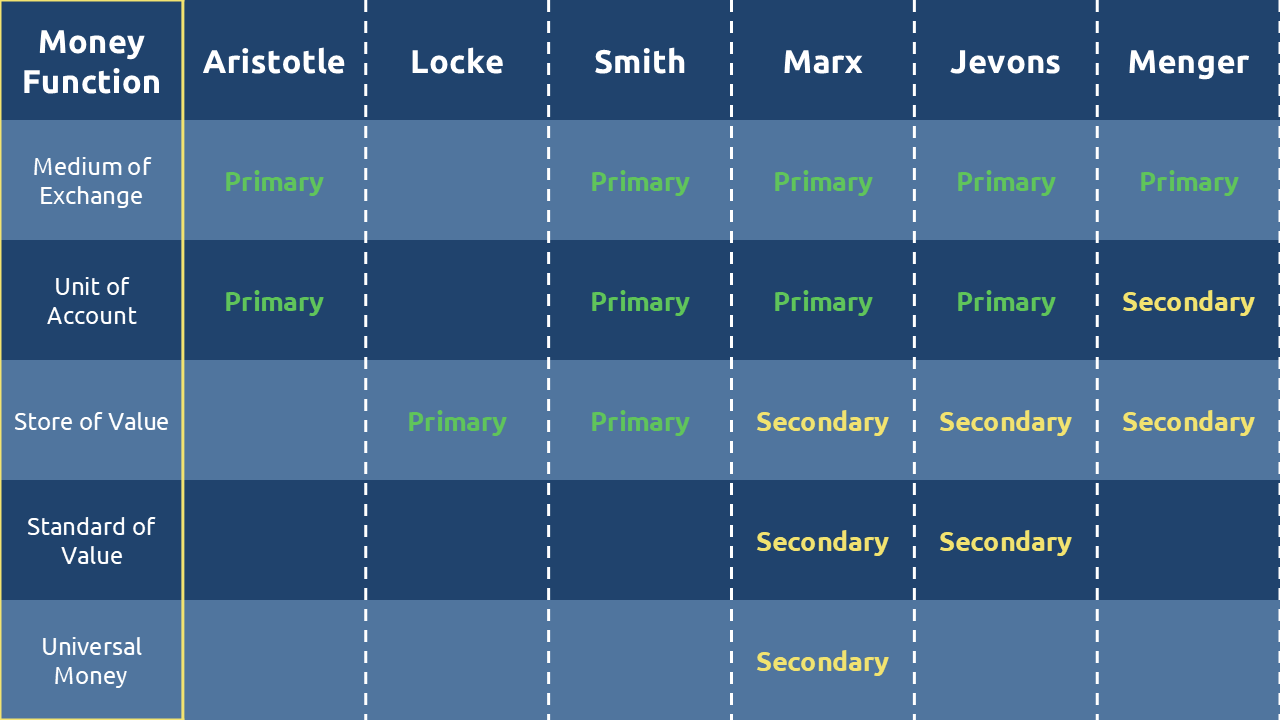

Money Functions

The theoretical framework for understanding money’s roles was constructed over centuries by foundational economic thinkers. Aristotle (384–322 BCE) is recognized as the earliest recorded theorist to systematically define money’s core purposes. In his works Nicomachean Ethics and Politics (c. 350 B.C.E.), he established that money serves two fundamental functions: as a unit of account and as a medium of exchange.

This framework was expanded nearly two millennia later by John Locke. In his Second Treatise of Government (1690), Locke introduced a third critical dimension, asserting that the primary purpose of money is to serve as a store of value.

The evolution of monetary theory culminated with Jevons in the 19th century. In his comprehensive work, Money and the Mechanism of Exchange (1875), Jevons identified and articulated a fourth essential function, defining money’s role as a standard of value. In his seminal work Capital (1867), Karl Marx identified a fifth, distinct function of money: to serve as a universal medium of payment in the global market.

Medium of Exchange

Aristotle positioned the function of a medium of exchange as money’s primary purpose, seeing it as a crucial instrument for facilitating trade and enabling broader social interaction. He conceptualized money as a solution to the inherent limitations and inefficiencies of the barter system. In Politics, Chapter X, he articulates a critical distinction:

“There are two sorts of wealth-getting, as I have said; one is a part of household management, the other is retail trade: the former necessary and honorable, while that which consists in exchange is justly censured; for it is unnatural, and a mode by which men gain from one another. The most hated sort, and with the greatest reason, is usury, which makes a gain out of money itself, and not from the natural object of it. For money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest. And this term interest, which means the birth of money from money, is applied to the breeding of money because the offspring resembles the parent. Wherefore of an modes of getting wealth this is the most unnatural.”

A clarification of these nuances is vital for the arguments in this series. Aristotle’s analysis is fundamentally teleological, from the Greek word “telos,” meaning the end or purpose of an action. He draws a sharp line between the natural use of money as a medium for obtaining real goods and services and what he saw as its perverse use, where money is employed in exchange solely to accumulate more money (as in usury or interest). In his view, money fulfills its true property only when it facilitates access to final goods and services. This property is broken when the exchange begins and ends with money itself, severing the connection to tangible value.

Whether one agrees with Aristotle’s moral stance on lending is secondary. The essential takeaway is his logical separation of money’s purposes – a conceptual framework we will revisit and apply throughout this series.

Unit of Account

The unit of account function of money originates from a fundamental need: to enable the exchange of items that are inherently unequal. Trade exists precisely because items are not equivalent; if they were, there would be no incentive to trade. Therefore, a just exchange is not one that makes the items equal, but one that accurately reflects and preserves their inherent, preexisting inequality. Money serves this purpose by providing a common denominator, a function that allows vastly different goods to be quantitatively compared as if they were qualitatively equivalent. This is the essence of the unit of account.

In Nicomachean Ethics, Book V, Aristotle explains this mechanism:

“This is why all goods must have a price set on them; for then there will always be exchange, and if so, association of man with man. Money, then, acting as a measure, makes goods commensurate and equates them; for neither would there have been association if there were not exchange, nor exchange if there were not equality, nor equality if there were not commensurability. Now in truth it is impossible that things differing so much should become commensurate, but with reference to demand they may become so sufficiently. There must, then, be a unit, and that fixed by agreement (for which reason it is called money); for it is this that makes all things commensurate, since all things are measured by money. Let A be a house, B ten minae, C a bed. A is half of B, if the house is worth five minae or equal to them; the bed, C, is a tenth of B; it is plain, then, how many beds are equal to a house, viz. five. That exchange took place thus before there was money is plain; for it makes no difference whether it is five beds that exchange for a house, or the money value of five beds.”

In essence, money makes fair and practical exchange possible. However, its deeper role is to create the very dimension – a standardized scale of value (or chreia) – on which the worth of all disparate goods can be quantitatively measured and compared, making complex exchange conceivable.

Store of Value

John Locke introduced a critical property that money must possess to effectively fulfill its role: durability. He argued that for wealth to be stored and preserved over time, the monetary instrument itself must be resistant to decay or spoilage. In his Second Treatise, Chapter V, Locke illustrates this principle:

“Again, if he would give his nuts for a piece of metal, pleased with its colour; or exchange his sheep for shells, or wool for a sparkling pebble or a diamond, and keep those by him all his life he invaded not the right of others, he might heap up as much of these durable things as he pleased; the exceeding of the bounds of his just property not lying in the largeness of his possession, but the perishing of any thing uselesly in it.

And thus came in the use of money, some lasting thing that men might keep without spoiling, and that by mutual consent men would take in exchange for the truly useful, but perishable supports of life.”

Locke’s analysis underscores a fundamental weakness of Vita money that prevented its mainstream adoption: its inherent perishability. Unlike durable commodities such as metals, gems, or shells, agricultural and pastoral wealth – nuts, sheep, wool – deteriorates over time. This perishability makes it a poor store of value, as accumulated wealth could literally spoil and be lost. Locke’s reasoning clearly favors metal money for its ability to preserve value indefinitely, a property that became a decisive factor in the evolution of monetary systems.

Standard of Value

Jevons identified an additional, critical function of money: to act as a standard of value. This function, which he categorized among the secondary monetary roles, provides a stable benchmark for deferred payments and long-term contracts. In Money and the Mechanism of Exchange, he explains the necessity of this standard:

“If corn be borrowed, corn might be paid back, with interest in corn; but the lender will often not wish to have things returned to him at an uncertain time, when he does not much need them, or when their value is unusually low. A borrower, too, may need several different kinds of articles, which he is not likely to obtain from one person; hence arises the convenience of borrowing and lending in one generally recognized commodity, of which the value varies little.”

It is noteworthy that Jevons uses Vita money – in this case, corn – as an example of a medium poorly suited for this role. He highlights its inherent flaw: value volatility driven by seasonal changes, harvest yields, and shifting demand. This variability makes it an unreliable unit for calculating debt or interest over time. In doing so, he implicitly argues for the superiority of alternative monies – particularly precious metals – that possess the essential quality of low variability in value, making them a stable and predictable standard for future obligations.

Universal Money

Carl Marx, in Capital, identified a distinct monetary function that becomes critical on the international stage: that of universal money. This concept focuses on money’s role as an accepted medium beyond local or national borders, facilitating global trade and settlement. Marx writes:

“Money of the world serves as the universal medium of payment, as the universal means of purchasing, and as the universally recognised embodiment of all wealth. Its function as a means of payment in the settling of international balances is its chief one. Hence the watchword of the mercantilists, balance of trade.”

Marx argued that for international trade and exchange, the ability of money to function as a universally accepted medium among nations constitutes a separate and vital function. This role demands a form of money whose value is recognized across different economic systems and political boundaries, primarily serving to settle international balances and act as a global means of payment.

Summary

Economic literature, from Aristotle to Carl Menger, contains extensive documentation of Vita money – such as cattle and grain – serving as active instruments of commerce. Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations, offers a clear example:

“In the rude ages of society, cattle are said to have been the common instrument of commerce; and, though they must have been a most inconvenient one, yet, in old times, we find things were frequently valued according to the number of cattle which had been given in exchange for them. The armour of Diomede, says Homer, cost only nine oxen; but that of Glaucus cost a hundred oxen.”

Despite this historical prevalence, Vita money ultimately yielded its role to gold and later fiat systems. As we will explore, this shift occurred because Vita forms of money failed to fully satisfy certain critical monetary functions required by more complex economies.

Theoretical perspectives on money functions vary significantly. Some economists, like Marx and Jevons, introduced additional roles such as standard of value or universal money. In contrast, scholars of the Austrian School – Menger, Mises, Rothbard – argued that the medium of exchange is the sole essential function, considering others mere derivatives. Aristotle himself would have dismissed the standard of value function, explicitly stating that money “was intended to be used in exchange… but not to increase at interest.”

Amid these divergent views, a modern consensus has largely coalesced around three core functions: medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value.

It is to the material properties that enable money to serve these functions that we now turn. By examining these properties, we can fully uncover why Vita money, despite its historical role, ultimately failed as sound money.

Money Properties

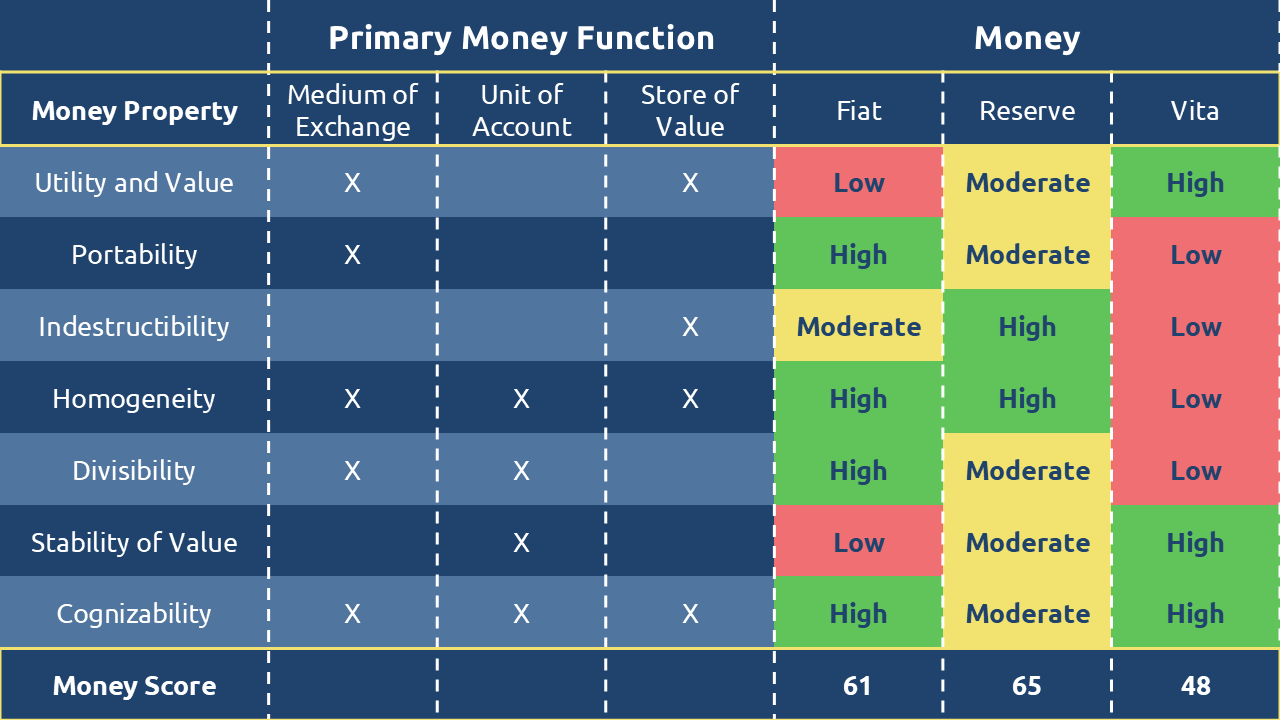

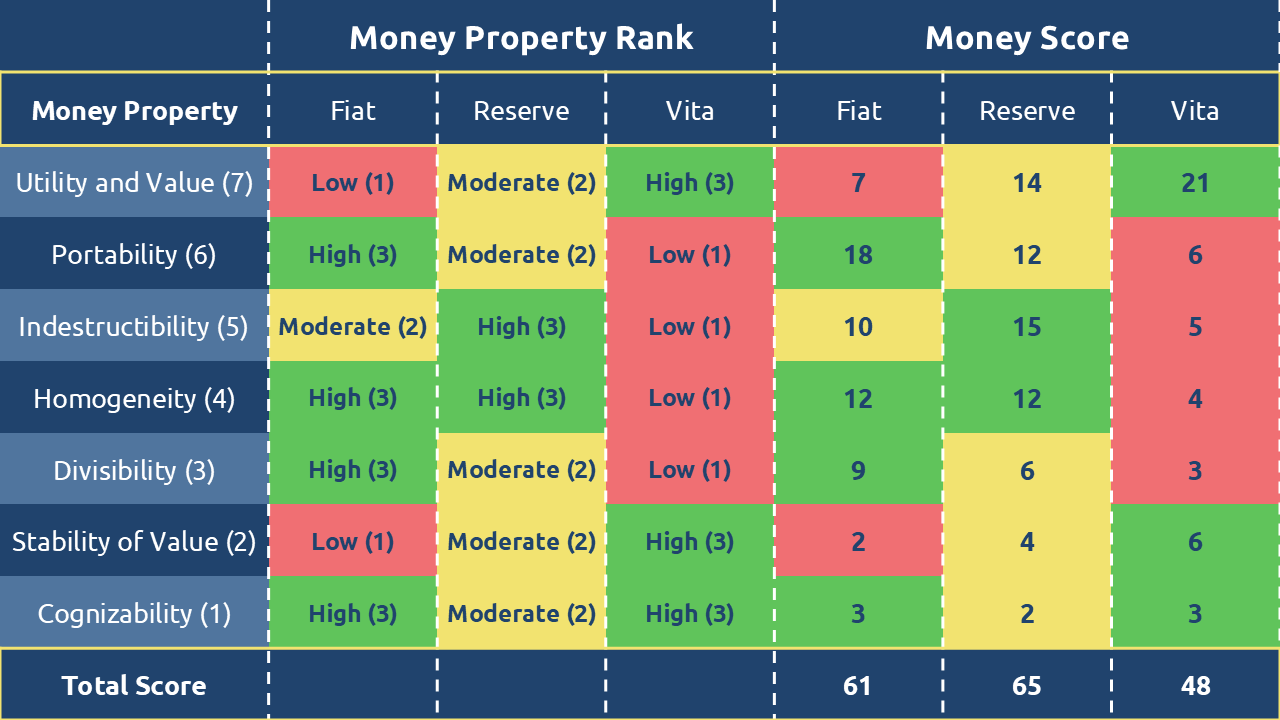

Later in his work, Jevons systematically outlines seven essential qualities that the material form of money should possess, listing them “in the order of their importance” as presented on Figure 5 (Jevons, 1875). To understand the failure of Vita money in the modern era, we must examine these fundamental properties and how they connect to the core functions of money.

By aligning these ideal monetary properties with the key functions they support, we can construct a clear framework for evaluating different forms of money. This analysis will reveal why Vita money ultimately lost ground to gold and, later, fiat currencies. For the purpose of this evaluation, we will focus on the properties most directly tied to the primary functions of money and will exclude the more specialized functions of standard of value and universal money, which are predominantly associated with debt structures and international payment systems.

Utility and value

According to Jevons: “Since money has to be exchanged for valuable goods, it should itself possess value, and it must therefore have utility as the basis of value.”

He argues that money must have inherent utility – value derived from its own practical use, independent of its role as a medium of exchange.

This is precisely where Vita money excels. It possesses not only intrinsic utility and value outside its monetary function but also the unique capacity for self-replication. This dynamic quality allows Vita to surpass Reserve currencies, which, though valuable, lack any inherent ability to regenerate or grow. This fundamental weakness is what leads many to dismiss fiat currency as merely “a piece of paper,” since its tangible value is negligible compared to the numerical value it represents.

Jevons himself recognized these inherent advantages of commodity-based money like Vita, noting:

“All the other articles mentioned in Chapter IV., such as oxen, corn, skins, tobacco, salt, cacao nuts, etc., which have performed the functions of money in one place or other, possessed independent utility and value.”

Solution for Vita

No solution is required; its inherent utility and self-replicating nature make it functionally superior in this regard.

Portability

Jevons identifies portability as a critical property, noting its importance extends beyond mere convenience to enabling large-scale and international trade. He writes:

“The portability of money is an important quality not merely because it enables the owner to carry small sums in the pocket without trouble, but because large sums can be transferred from place to place, or from continent to continent, at little cost. The result is to secure an approximate uniformity in the value of money in all parts of the world.”

This characteristic – the ease with which money can be transported – is fundamental to facilitating exchange. While Vita money served adequately within local economies and short-distance trade, it faced insurmountable challenges as commerce expanded globally. Transporting cattle across oceans or moving large quantities of grain over long distances was impractical and costly. This limitation created an opportunity for metal-based money, which offered superior portability.

Carl Menger, in The Origins of Money, highlights the advantages of precious metals in this regard:

“Besides this there are the wide limits in time and space of the saleableness of the precious metals; a consequence, on the one hand, of the almost unlimited distribution in space of the need for them, together with their low cost of transport as compared with their value, and on the other hand, of their unlimited durability and the relatively slight cost of hoarding them.”

Solution for Vita

The inherent nature of many forms of Vita money – being bulky, perishable, or difficult to divide – poses a fundamental challenge to portability. However, history shows a viable workaround: the creation of claims on stored Vita assets.

A prime example is the tobacco standard in colonial America. Tobacco officially served as money in Virginia starting in 1618, with its value set by government proclamation. However, the physical difficulty of transporting large quantities of tobacco led to the development of paper alternatives. Rather than moving the actual crop, traders used promissory notes that were payable in tobacco. This system evolved further with the establishment of public warehouses. Depositors would store their tobacco and receive a warehouse receipt – a paper document representing a claim on the stored commodity. These receipts soon began circulating as money themselves, functioning as a portable, tobacco-backed currency in Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, and beyond.

This innovation effectively decoupled Vita’s value from its physical form, solving the portability problem through representation rather than attempting to alter the physical properties of the commodity itself.

Indestructibility

Economists more commonly refer to this essential property as durability rather than indestructibility. Jevons articulates why this quality is fundamental:

“If it is to be passed about in trade, and kept in reserve, money must not be subject to easy deterioration or loss. It must not evaporate like alcohol, nor putrefy like animal substances, nor decay like wood, nor rust like iron. Destructible articles, such as eggs, dried codfish, cattle, or oil, have certainly been used as currency; but what is treated as money one day must soon afterwards be eaten up.”

Jevons correctly identifies the inherent challenge with many forms of Vita money: their natural tendency to perish. This vulnerability to decay and spoilage presents a significant obstacle to serving as a reliable store of value.

John Locke similarly recognized this limitation while suggesting how certain Vita commodities might offer extended durability:

“And if he also bartered away plums, that would have rotted in a week, for nuts that would last good for his eating a whole year, he did no injury; he wasted not the common stock; destroyed no part of the portion of goods that belonged to others, so long as nothing perished uselesly in his hands. “

Jevons himself noted exceptions among Vita forms, observing that “The several kinds of corn are less subject to this objection, since, when well dried at first, they suffer no appreciable deterioration for several years.”

Solution for Vita

It is important to recognize that no form of money is perfectly durable without proper maintenance. Precious metals can be scratched, corroded, or otherwise damaged, reducing their value. Modern fiat currencies also deteriorate – older banknotes may be rejected by official institutions or heavily discounted in unofficial markets due to wear and susceptibility to counterfeiting.

Modern technology offers solutions to Vita’s historical durability challenges. Refrigeration and freezing technologies can extend the lifespan of perishable Vita commodities dramatically – frozen meat, for instance, can remain preserved for decades. Additionally, Vita’s unique property of self-replication partially offsets perishability concerns by continuously generating new value.

While durability posed a significant challenge to Vita money historically, modern preservation methods and Vita’s inherent capacity for regeneration substantially mitigate this limitation in contemporary contexts.

Homogeneity

The property of homogeneity is more commonly referred to by economists as fungibility. Jevons emphasizes its critical importance:

“All portions of specimens of the substance used as money should be homogeneous, that is, of the same quality, so that equal weights will have exactly the same value. In order that we may correctly count in terms of any unit, the units must be equal and similar, so that twice two will always make four.”

This presents a particular challenge for many forms of Vita money. Consider livestock: a female sheep holds different value than a male sheep; dominant rams command different worth than subordinate ones; animals vary in size, weight, wool production, and health. This inherent variability complicates their function as uniform monetary units.

Menger highlights the advantage of precious metals in this regard: “Moreover the homogeneity of precious metals, and the consequent facility with which they can serve as res fungibiles in relations of obligation, have led to forms of contract by which traffic has been rendered more easy; this too has materially promoted the saleableness of the precious metals, and thereby their adoption as money.”

Solution for Vita

Jevons notes that cattle were historically standardized through simple counting: “showing the importance of live-stock in a primitive state of society. Being counted by the head, the kine was called capitale, whence the economical term capital, the law term chattel, and our common name cattle.”

A more sophisticated approach emerged with grain-based Vita money through standardized weights and measures. The ancient shekel, originating from the Akkadian word for barley, began as a precise unit of measurement equivalent to 180 grains of barley (approximately 11 grams). This standardization allowed barley to transcend its physical form and become a recognized monetary standard throughout Mesopotamia as early as 3000 BC.

Modern proposals continue this tradition of standardization. The Grain Commodity Standard (GES) initiative, for instance, proposes using one ton of grain as a monetary unit. This approach finds theoretical support in Keynes’s Tract on Monetary Reform, where he suggested that authorities adopt the composite commodity:

“Nevertheless, whilst it would not be advisable to postpone action until it was called for by an actual movement of prices, it would promote confidence and furnish an objective standard of value, if, an official index number having been compiled of such a character as to register the price of a standard composite commodity, the authorities were to adopt this composite commodity as their standard of value in the sense that they would employ all their resources to prevent a movement of its price by more than a certain percentage in either direction away from the normal, just as before the war they employed all their resources to prevent a movement in the price of gold by more than a certain percentage. The precise composition of the standard composite commodity could be modified from time to time in accordance with changes in the relative economic importance of its various components.”

Through careful measurement, grading, and standardization, Vita money can achieve the fungibility necessary for modern monetary functions, transforming variable natural products into consistent units of account.

Divisibility

Jevons addresses the nuanced requirement of divisibility in monetary substances: “Every material is, indeed, mechanically divisible, almost without limit. The hardest gems can be broken, and steel can be cut by harder steel. But the material of money should be not merely capable of division, but the aggregate value of the mass after division should be almost exactly the same as before division.”

This presents a significant challenge for many forms of Vita money. While grains and agricultural products can be divided relatively easily, the divisibility of livestock poses a substantial obstacle. One cannot divide a living animal without destroying its value entirely.

Adam Smith elaborates on this practical limitation: “He could seldom buy less than this, because what he was to give for it could seldom be divided without loss; and if he had a mind to buy more, he must, for the same reasons, have been obliged to buy double or triple the quantity, the value, to wit, of two or three oxen, or of two or three sheep. If, on the contrary, instead of sheep or oxen, he had metals to give in exchange for it, he could easily proportion the quantity of the metal to the precise quantity of the commodity which he had immediate occasion for.”

Solution for Vita

The inherent divisibility limitations of certain Vita forms, particularly livestock, could be addressed through representative instruments such as notes (similar to gold-backed certificates) or tally sticks. These instruments would represent claims on divisible units of Vita value without requiring physical division of the assets themselves.

However, such solutions introduce their own complexities regarding trust, verification, and institutional support, which we will explore further in subsequent sections. The most practical approach may involve focusing on naturally divisible forms of Vita money, such as grains or other vegetation produce, which can be divided and recombined without significant loss of value. These forms of Vita money offer better inherent divisibility characteristics for modern monetary applications.

Stability of value

Jevons emphasizes the importance of this monetary property: “It is evidently desirable that the currency should not be subject to fluctuations of value. The ratios in which money exchanges for other commodities should be maintained as nearly as possible invariable on the average.”

Stability of value is fundamentally connected to money’s functions as both a unit of account and a store of value. In this crucial aspect, Vita money demonstrates superior performance compared to both fiat and reserve currencies. Because its value is inherently tied to real economic production and biological growth cycles within a society, Vita money maintains a more stable relationship with the actual goods and services in an economy.

Carl Menger, while acknowledging the relative stability of precious metals, notes: “This development was materially helped forward by the ratio of exchange between the precious metals and other commodities undergoing smaller fluctuations, more or less, than that existing between most other goods, – a stability which is due to the peculiar circumstances attending the production, consumption, and exchange of the precious metals, and is thus connected with the so-called intrinsic grounds determining their exchange value.”

Solution for Vita

No solution required. Vita’s inherent connection to real economic production and its self-replicating nature provides natural stability that outperforms both commodity metals and government-issued fiat currencies in maintaining long-term value stability.

Cognizability

Jevons defines cognizability as: “By this name we may denote the capability of a substance for being easily recognized and distinguished from all other substances. As a medium of exchange, money has to be continually handed about, and it will occasion great trouble if every person receiving currency has to scrutinize, weigh, and test it.”

In this regard, many forms of Vita money excel. Cattle are immediately recognizable and difficult to counterfeit. Most grain types are similarly easily identifiable to those familiar with agricultural products. This stands in contrast to precious metals like gold, which require careful examination, weighing, and testing to verify authenticity – a process vulnerable to deception through techniques such as plating or alloying, methods historically exploited by monarchs and counterfeiters.

Carl Menger acknowledges the recognizability of precious metals, though with qualification: “Finally the precious metals, in consequence of the peculiarity of their colour, their ring, and partly also their specific gravity, are with some practice not difficult to recognise, and through their taking a durable stamp can be easily controlled as to quality and weight; this too has materially contributed to raise their saleableness and to forward the adoption and diffusion of them as money.”

Solution for Vita

No solution required. The immediate recognizability of most Vita forms – from livestock to staple crops – provides inherent protection against counterfeiting and facilitates ease of transaction verification, making Vita money naturally superior in cognizability compared to precious metals.

Money Score

Using a weighted scoring model based on Jevons’ hierarchy of monetary properties where the most important property (utility and value) carries the highest weight and the least important (cognizability) the lowest, each monetary type was evaluated. Performance for each property was rated on a scale of 3 (highly satisfactory) to 1 (low satisfaction). The results of this analysis (mentioned in Figure 5 and detailed in Figure 6) are as follows:

- Reserve Money achieved the highest score: 65

- Fiat Money followed with a score of: 61

- Vita Money ranked last with a score of: 48

According to this conventional assessment framework, even fiat currency appears superior to Vita money. This quantitative result invites deeper investigation into the underlying reasons why Vita failed to become the dominant form of money in the modern era, despite its theoretical advantages in certain properties.

Vita Limitations

Beyond the specific property mismatches previously analyzed, Vita money faces several fundamental limitations that likely contributed to its declining adoption over time. These structural challenges extend beyond the basic monetary properties and address deeper practical constraints in implementing Vita-based monetary systems.

Maintenance

The most significant barrier to Vita’s adoption is the substantial maintenance it demands. While storing agricultural produce may seem straightforward, preserving it under conditions that enable self-replication presents considerable challenges. The same applies to livestock: maintaining and breeding cattle requires significantly more active management than safeguarding gold or even managing fiat currency systems.

This maintenance burden likely represents the primary reason Vita failed to achieve monetary dominance. As an increasingly large proportion of the global population moved away from agricultural occupations toward specialized urban trades, the practical expertise and daily effort required to maintain self-replicating monetary assets became prohibitive for most users. The passive storage requirements of metal-based money and the administrative nature of fiat systems ultimately proved more compatible with modern economic specialization and urbanization patterns.

Finality of Settlement

Although Vita functioned as the earliest form of money, its inherent limitations in divisibility and portability likely prompted the development of representative note systems even within small tribal communities. In these intimate social structures, trust and reputation functioned as powerful enforcement mechanisms – untrustworthy individuals faced severe consequences, including ostracization that could lead to vulnerability, hunger, or attack.

However, as human communities expanded beyond close-knit tribal networks, these informal reputation systems became inadequate for supporting Vita-based note systems. The scaling of societies necessitated the creation of formal institutions – trade settlement bodies and judicial courts – to verify and enforce transactions involving Vita-backed instruments.

This institutional requirement introduced a critical inefficiency: a settlement authority would need to verify and record every transaction to maintain the integrity of the system and effectively create divisibility for bulk Vita assets. This procedural burden would inevitably reduce transaction velocity, potentially creating friction that could slow economic activity and limit the scalability of Vita-based monetary systems in growing civilizations.

Universal Availability

As economic systems expanded beyond local and regional boundaries, a fundamental challenge emerged: different nations and regions produced and valued different commodity sets. For Vita money to function in global trade, the same specific commodity would need to be universally available and recognized – a requirement that proved increasingly difficult to fulfill.

This limitation elevated the importance of monetary properties like portability, divisibility, and durability, which became critical for facilitating cross-border exchange. Without a universally available commodity standard, the unit of account function would be severely compromised. Inconsistent availability would lead to inefficient price discovery mechanisms, creating substantial arbitrage opportunities that would destabilize value measurements across economic regions. The resulting price disparities would undermine Vita’s effectiveness as a reliable unit of account in an increasingly interconnected global economy.

Network Effect

When Jevons published his work in the 19th century, digital money remained unimaginable. He explicitly framed his analysis within the constraints of physical properties, noting: “The prevailing defect in the treatment of the subject is the failure to observe that money requires different properties as regards different functions. To decide upon the best material for money is thus a problem of great complexity, because we must take into account at once the relative importance of the several functions of money, the degree in which money is employed for each function, and the importance of each of the physical qualities of the substance with respect to each function.”

Evaluated solely through this material-world lens, reserve money (particularly gold) emerged as the optimal choice. Having objectively lost this competition under historical technological constraints, Vita money largely disappeared from monetary scholarship. Jevons himself devoted approximately 500 words to commodity money like Vita compared to 13,750 words analyzing metal coins.

The network effect proves more powerful than often acknowledged. Once a monetary standard becomes established, game theory suggests that switching requires coordination among a majority of influential economic players (approaching 51%). Alternatively, a self-contained economic bloc (similar to BRICS) could establish a new standard independently, even while representing a minority of nations, provided it encompasses sufficient economic mass.

Historical precedent confirms this dynamic: the American colonies initially implemented a tobacco standard in the 1700s, but ultimately adopted the gold standard to participate effectively in global trade. This transition reflected network dominance rather than any inherent superiority of gold.

The Web3 breakthrough fundamentally changes this equation by resolving most traditional monetary limitations through digital innovation. This technological leap invites a crucial re-examination: how would a Web3-enabled Vita currency compare to its digital fiat and reserve counterparts in the modern era?