The Dream of Self-Replicating Scarcity

What if scarcity could compound?

We prize inelastic assets – like gold – for their resistance to inflation. But what if an inelastic asset could generate additional inelastic units intrinsically? Not through mining (which requires selling your original position) or financial leverage (which introduces risk), but through self-replication.

Gold’s Inelastic Dead End

Gold’s scarcity is its virtue – but also its limitation. To “grow” your gold holdings, you could either sell part of your stack to fund miners, reducing your inelastic base or borrow against it, betting future prices will cover debt costs – a gamble that contradicts inelasticity’s purpose (price stability).

Both strategies fail because gold produces no yield – it’s inert, while debt demands elasticity – the very thing inelastic money avoids.

The Vita Paradox

Inelastic assets protect wealth, but cannot grow it without compromising their core feature. Vita Money resolves this – imagine gold that replicates itself while retaining absolute scarcity.

Introducing Vita Money: Self-Replicating Scarcity

Picture this: You store one gold bar in a vault, untouched. A year later, you return – and now two bars sit where one once lay. This is Vita Money: an asset that does not just store value but generates more of itself while retaining inelasticity.

Beyond the Golden Goose

The old fable tells of a goose that lays golden eggs – a metaphor for yield without growth. But Vita Money works differently:

- Golden Goose → Produces eggs (cash flow), but each new egg dilutes the value of existing gold.

- Vita Goose → Produces more geese (new units of capital), exponentially expanding wealth without inflation.

The fable’s true irony reveals a profound economic insight: the goose ultimately outweighs the gold in long-term value. While a golden egg might command immediate wealth, the goose represents something far more powerful – self-sustaining capital.

Preservation vs. Multiplication

This distinction between static treasure and productive asset defines the Vita Money principle. A single golden egg delivers finite value, but a living goose generates:

- Exponential growth through reproduction

- Perpetual yield without depletion

- Network effects of an expanding flock

A golden egg is a static reserve asset – it maintains purchasing power but does not grow it. A Vita Goose, however, reproduces itself, creating an expanding flock. Over time, you don’t just preserve wealth – you compound it, with the option to liquidate into traditional reserves (golden eggs) at will.

This is the power of self-multiplying scarcity: money that breeds more money, yet never loses its fundamental rarity.

The Agricultural Origins of Vita Money

The earliest prototype of Vita Money emerged from humanity’s first economic systems – agricultural wealth that could biologically reproduce. Historical evidence shows:

Livestock as Living Currency

- Ancient Mesopotamian clay tokens (c. 3000 BCE), described by some scholars as the world’s first money, used sheep as standard value measures (one token was equivalent to one sheep)

- Indo-European “peku” (livestock) became the root for both “pecuniary” and the Latin “pecunia” (money)

- As recently as 20th-century in countries of Africa (e.g. Kenya) and Eurasia (e.g. Mongolia), bridewealth payments of livestock remained standard

Seed-Based Monetary Systems

- Early Chinese dynasties (as early as 1600 – 1046 BCE) used measured bushels of grain for tax payments

- Ancient Egyptians used wheat and credits based on wheat as the blood of their complex banking and financial system.

- Aristotle noted grain’s dual role as both commodity and money standard

In Politics, Aristotle articulates his seminal critique of monetized exchange, condemning the unnatural diversion of goods from their proper ends. He observes how the invention of coinage enabled a new class of intermediaries who profit not through production, but through the manipulation of exchange itself – what he terms kapēlikē (retail trade).

This development, he argues, corrupts the natural order by divorcing economic activity from the true purpose of goods:

“Others maintain that coined money is a mere sham, a thing not natural, but conventional only, because, if the users substitute another commodity for it, it is worthless, and because it is not useful as a means to any of the necessities of life, and, indeed, he who is rich in coin may often be in want to necessary food. But how can that be wealth of which a man may have a great abundance and yet perish with hunger. Like Midas in the fable, whose insatiable prayer turned everything that was set before him into gold?”

Key Differentiators in Agricultural Money

Ancient Commodities Overview

| Asset Type | Growth Rate | Recreation Cycle | Storage Durability |

| Sheep Flocks | 15-30% annual growth | 150 days | 5-10 year lifespan |

| Cattle Herds | 5-10% annual growth | 280 days | 10-15 year lifespan |

| Wheat Stores | 100% seasonal yield | 120 days | 2-3 year shelf life |

Why This Matters

These systems were not primitive barter. They represented sophisticated understanding of:

- Predictable scarcity (hard caps on reproduction)

- Time value of assets (slow cattle vs. faster sheep liquidity)

- Inelastic supply (cannot artificially accelerate growth)

The transition to metal currency sacrificed this self-replicating property for durability – a trade Vita Money seeks to reconcile in digital form.

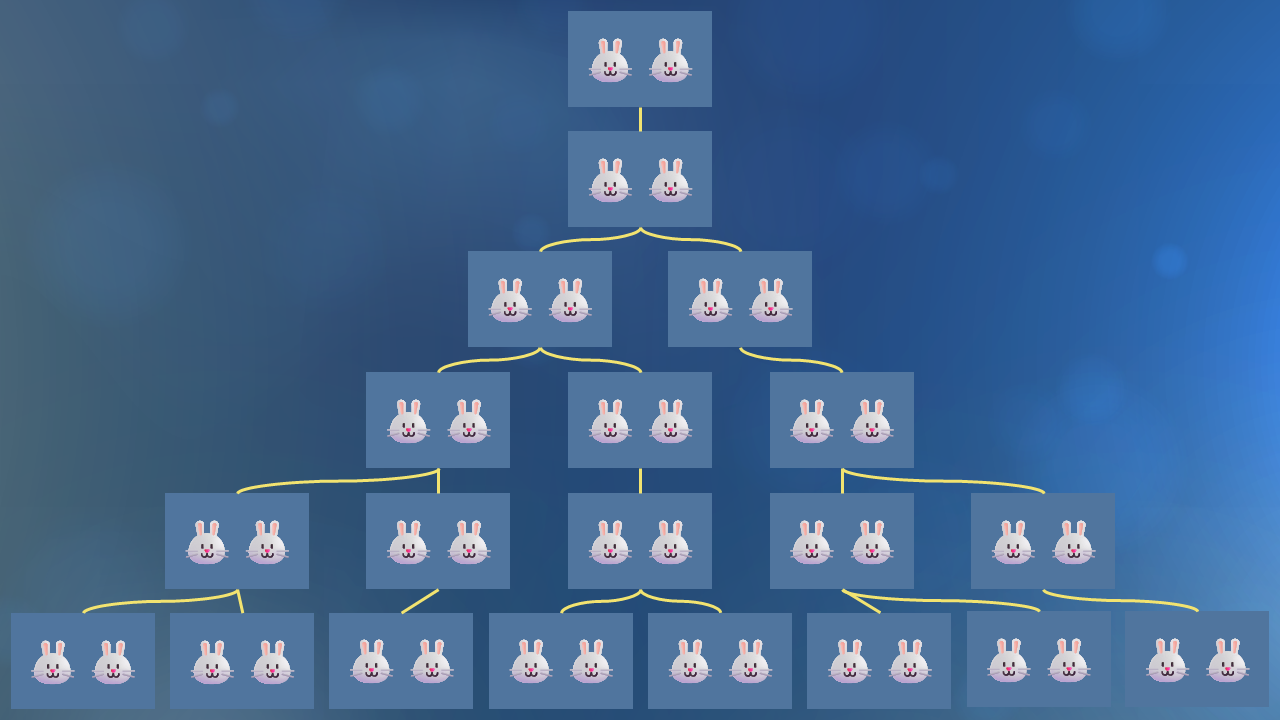

Fibonacci’s Rabbits

In 1202, Leonardo of Pisa posed a deceptively simple question: If you place one pair of rabbits in a field, how many will you have in a year? His answer – the Fibonacci sequence – unwittingly described the perfect Vita Money system centuries before the concept existed.

The rules mirrored ideal monetary properties:

- Self-replication: Each mature pair produces new pairs monthly

- Time-locked growth: New pairs require a full month to mature

- Organic scarcity: Population grows exponentially yet predictably

By month 12, the original pair multiplies into 144 – not through arbitrary issuance, but through nature’s disciplined rhythm of creation. This wasn’t just mathematics; it was a blueprint for money that breathes, grows, and sustains its value through inherent reproductive logic.

Where golden eggs represent inflationary yield, Fibonacci’s rabbits model non-dilutive expansion – the core innovation Vita Money seeks to digitize. The sequence’s enduring relevance proves what ancient pastoralists understood: True wealth reproduces itself on nature’s schedule, not banker’s whims.

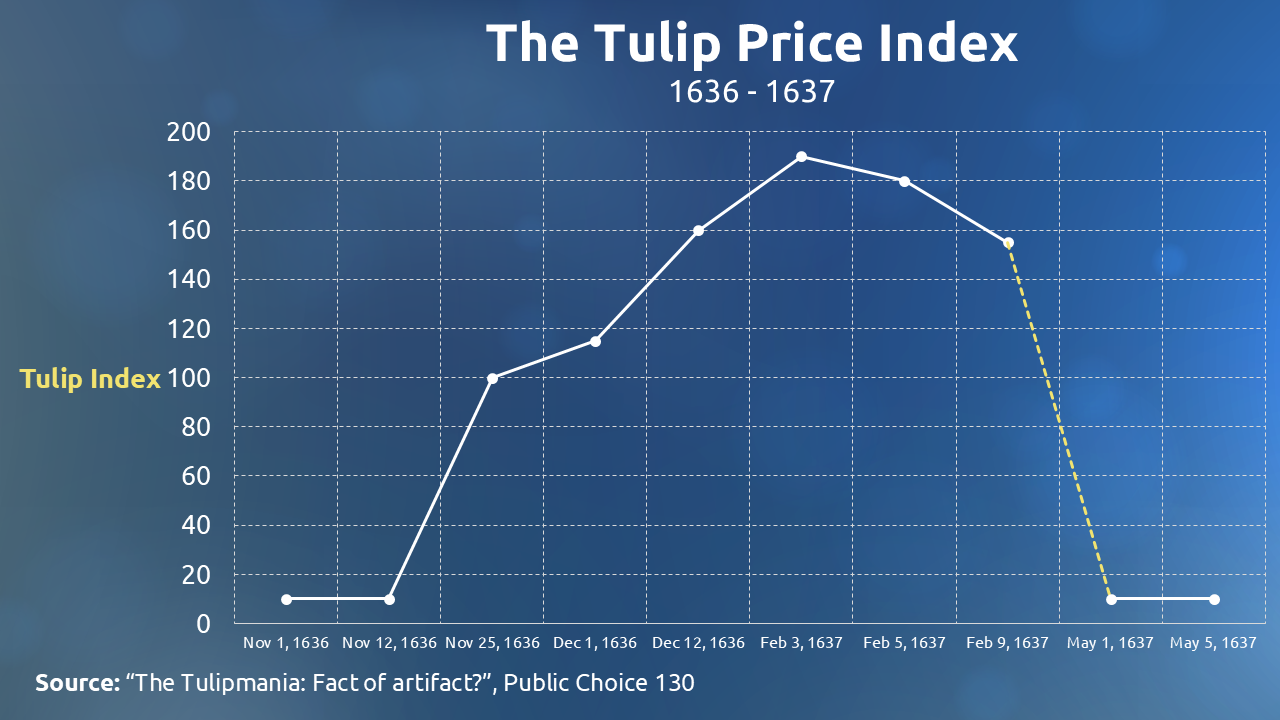

Tulip Mania Reexamined

The lazy comparison between cryptocurrencies and Tulip Mania misses a crucial distinction: tulips were not merely speculative bubbles – they were Vita Money in its purest biological form. When critics dismiss Bitcoin as “digital tulips,” they reveal their ignorance of monetary history.

Tulips could never function as reserve currency (e.g. gold, Bitcoin); their value derived instead from their capacity as self-replicating assets. The 17th century frenzy occurred precisely because participants recognized tulips’ Vita properties: bulbs that reliably produced new units of value while maintaining scarcity. This organic multiplication mechanism, not irrational exuberance alone, drove the mania.

While tulips became synonymous with Dutch culture, their origins trace back to the Ottoman Empire. The flowers first arrived in the Netherlands from Constantinople as exotic luxury goods in the late 1500s. This foreign provenance proved crucial to their appeal. As imported novelties rather than common local blooms, tulips carried intrinsic rarity that fueled their eventual Vita Money status. The very fact that they were not native Dutch flowers created the scarcity conditions necessary for their monetary properties to emerge.

Contrary to popular belief, the 1637 tulip crash did not cripple the Dutch economy. While many individual speculators faced ruin – particularly those who had traded on margin – the Netherlands’ financial system remained intact.

The Netherlands emerged from tulip mania to become the world’s floral superpower. Today, this small nation dominates global flower markets with astonishing efficiency:

Floral Trade Hegemony

- Controls 44% of worldwide floricultural trade

- Supplies 77% of all flower bulbs (with tulips remaining the crown jewel)

Innovation Leadership

- Develops 65% of Europe’s new plant varieties annually (~1,800 cultivars)

- Maintains €6 billion in annual floral exports

This transformation from speculative frenzy to agricultural powerhouse proves a vital economic lesson: market manias come and go, but fundamentally sound assets endure.

All monetary innovations endure speculative phases:

- Gold witnessed multiple bubbles before becoming a reserve standard

- Bitcoin survived early “tulip” comparisons to achieve institutional adoption

- Even the U.S. dollar had its wildcat banking crises

The lesson? Mania is a feature of human psychology, not a flaw in the asset. Tulips failed as currency not because they lacked Vita properties – their biological scarcity and reproductive yield were sound – but because futures contracts detached pricing from natural growth cycles. When speculation outpaces an asset’s fundamental replication rate, the system breaks.

The Fundamental Properties of Vita Money

Vita Money is defined by two essential characteristics: inelasticity and self-replication. These properties distinguish it from conventional forms of money and give it unique monetary advantages—if properly understood.

Self-Replication

Like all life, Vita Money follows nature’s principle of regeneration. Animals produce offspring, plants yield seeds that become new life; and in the same way, Vita replicates itself. This organic growth mechanism ensures that the money supply can expand naturally, without artificial inflation.

Inelasticity

Yet, unlike fiat currencies (which central banks can print at will) or even gold (which mining technology has made more abundant), Vita’s growth is constrained by natural limits. Crops follow seasons; livestock reproduce at fixed biological rates.

As Warren Buffett famously observed: “You can’t produce a baby in one month by getting nine women pregnant.”

But this raises a critical question: How can something be both self-replicating and inelastic? Doesn’t self-replication imply elasticity?

The Myth of Elasticity in Vita Money

At first glance, livestock appears to be an elastic commodity. After all, cattle and sheep can be bred in large numbers. If demand increases, shouldn’t supply follow suit? This superficial logic suggests that Vita assets (like cattle or sheep) could never function as sound money because their supply seems infinitely expandable.

But this perception is a modern illusion.

The False Promise of Elastic Livestock

Today, industrial farming has warped our understanding of natural scarcity:

- Cattle and sheep production appears elastic because anyone can theoretically breed more animals.

- When prices rise, more farmers enter the market, increasing supply and driving prices back down.

- This price sensitivity makes livestock seem unsuitable as a stable monetary base, which is precisely why gold and fiat eventually replaced Vita-based money.

Technology’s Distortion of Scarcity

However, this elasticity is not inherent. It’s an artificial byproduct of modern industrialization:

- Only a century ago, meat was scarce. Livestock grew at nature’s pace, constrained by disease, seasons, and land.

- The 20th century changed everything. Hormones, antibiotics, and factory farming turned livestock into a scalable commodity just as mining advancements inflated gold supply.

- We now mistake industrial abundance for natural elasticity. But true, organic Vita assets remain bound by biological limits.

The same forces that made gold elastic (through mass mining) also made livestock elastic (through industrial farming). This doesn’t mean Vita is fundamentally elastic. It simply demonstrates how modern production methods have masked its true scarcity.

The Elasticity Illusion

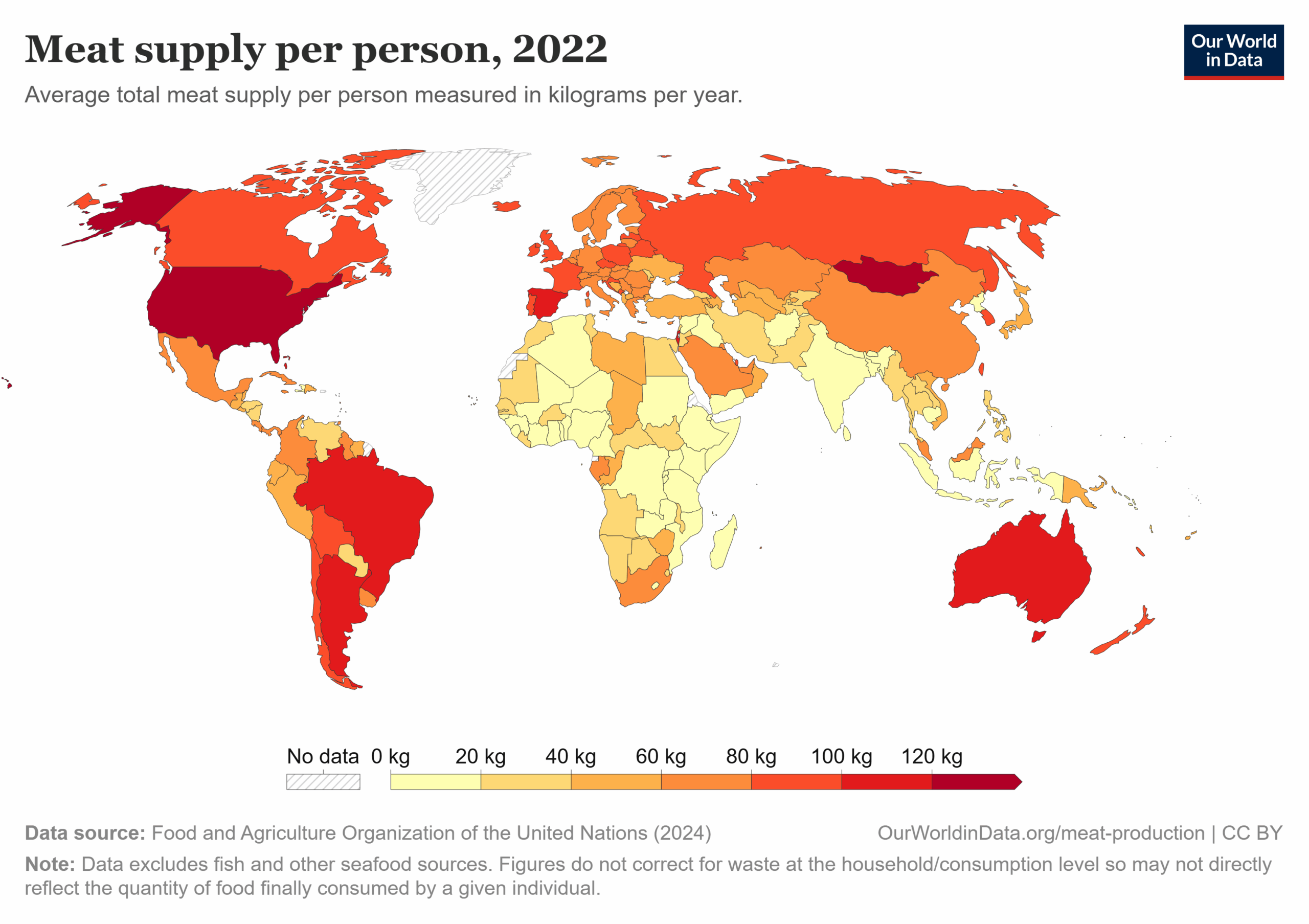

The assumption that Vita money exhibits elastic properties collapses under scrutiny when examining global meat distribution patterns. While developed nations enjoy abundant meat supplies – visible in every supermarket across North America, Europe, and Oceania – this abundance represents a geographic anomaly rather than a universal condition.

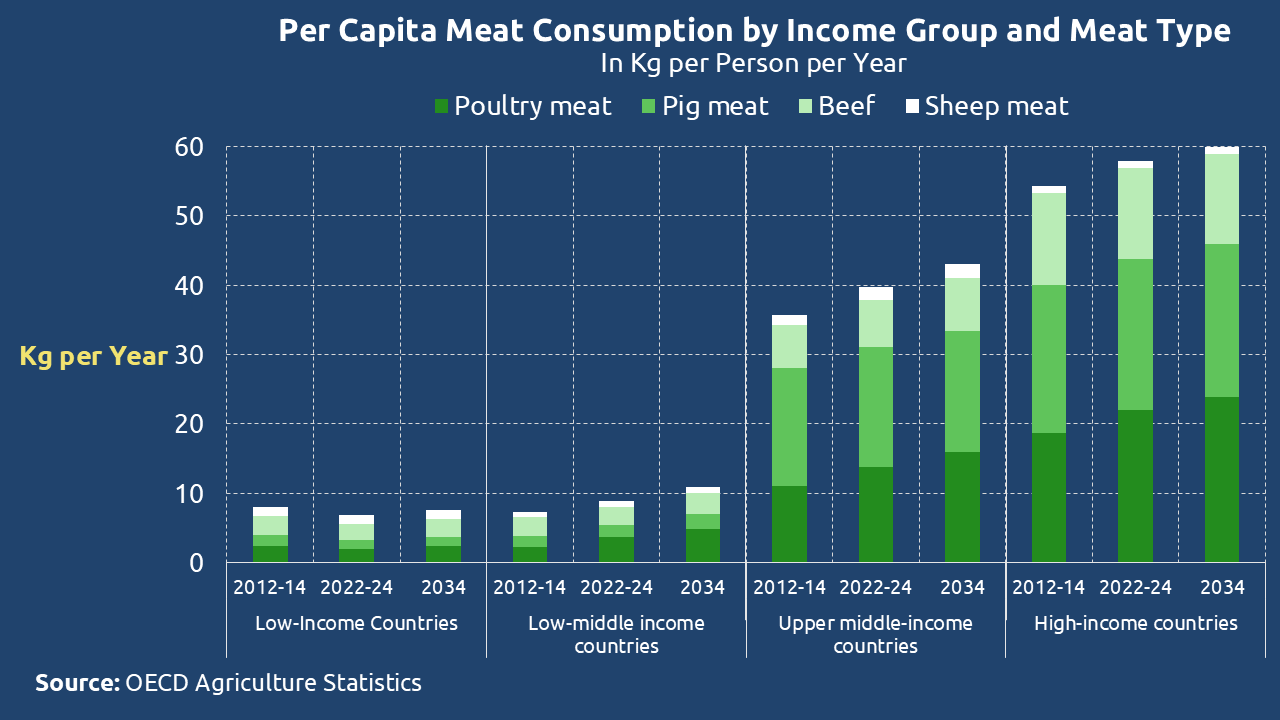

The data reveals a stark dichotomy: high-income nations consume meat at rates three times greater than lower-income countries, with projections showing this disparity still persisting through 2034 (Figure 3 & Figure 4). This isn’t merely an economic imbalance, it’s evidence of structural inelasticity. When 3.3 billion people consume less than 20kg of meat annually per person (FAO 2022), while simultaneously living in an era of AI and robotics revolutions, we witness the fundamental scarcity of true Vita assets.

The roots of this scarcity run deep. Centuries of economic systems designed by colonial powers continue to enforce protein poverty across resource-rich regions. No amount of modern farming technology has overcome these fundamental constraints. The apparent “elasticity” in Western markets represents not true abundance, but concentrated allocation within privileged economies.

When we measure Vita across the entire global system – accounting for both production and equitable distribution – its essential inelasticity becomes undeniable. What appears as flexible supply in isolated markets is actually scarcity made invisible through economic stratification.

True Vita money, like all natural systems, operates within fixed biological boundaries that no financial or political system can ultimately circumvent.

True Vita money, when measured across the entire planetary system, demonstrates both fundamental and practical inelasticity.

The Quantity-Quality Deception

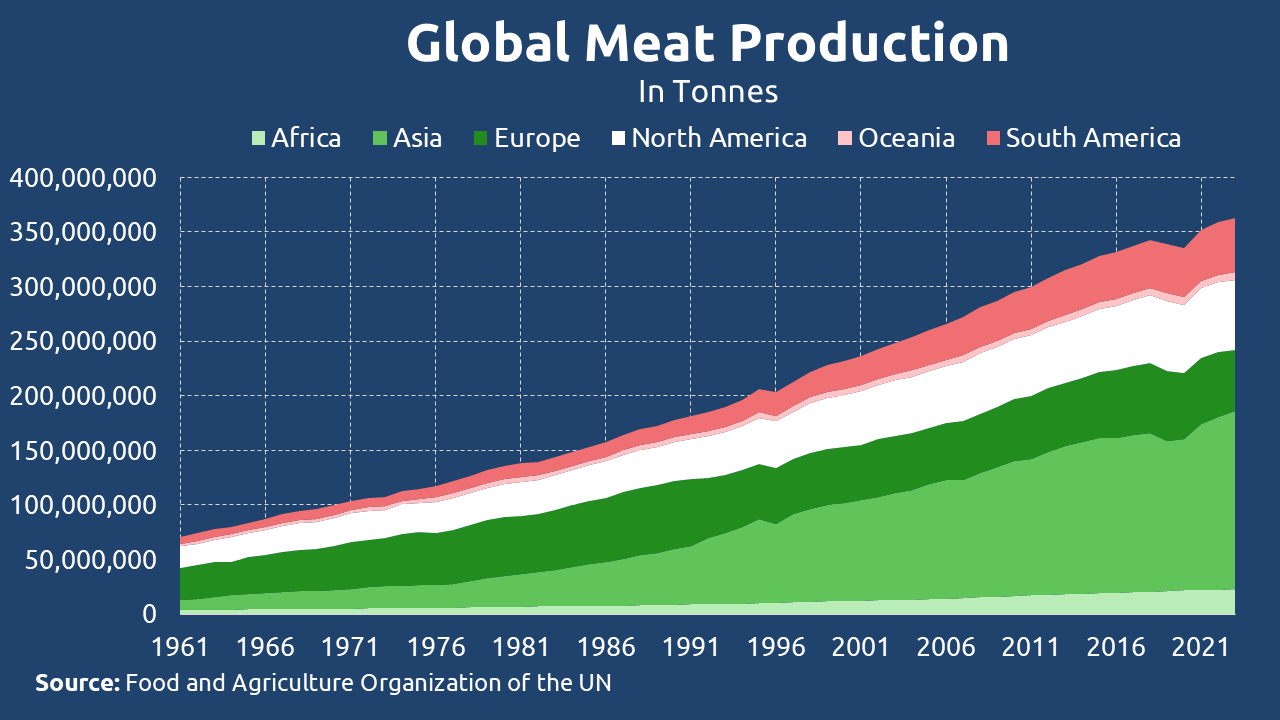

UN data appears to contradict Vita’s inelastic nature. Global meat production has skyrocketed from 70 million tonnes in 1961 to over 360 million tonnes today (Figure 5). This five-fold increase might suggest perfect elasticity, but this interpretation misses a crucial distinction: modern livestock units bear little resemblance to their historical counterparts.

The industrial meat revolution came at a hidden cost. What we count as “meat production” today includes:

- Hormone-injected animals reaching slaughter weight in half the time

- Grain-fed livestock with altered nutritional profiles

- Meat products extended with preservatives and additives

This represents a fundamental quality dilution, comparable to accepting 50% purity gold as equivalent to historical 100% pure gold. The organic meat movement emerged precisely to preserve the authentic, chemical-free quality our ancestors considered the norm.

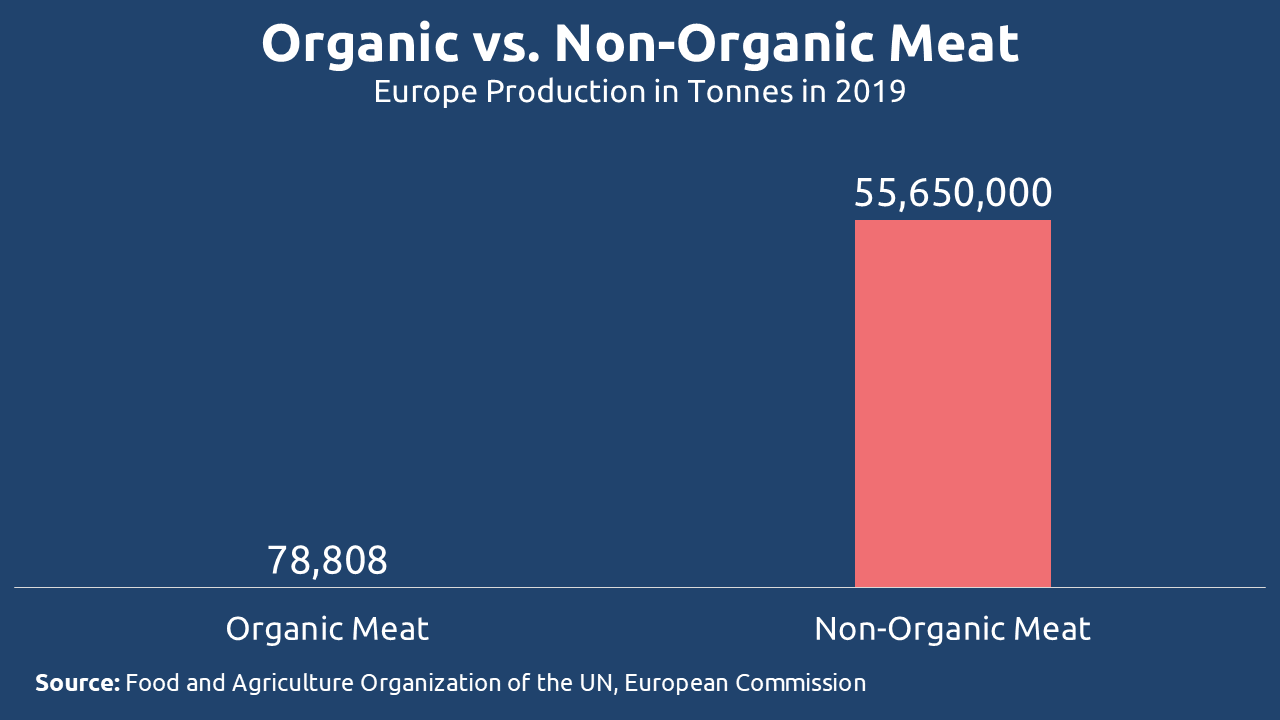

The numbers reveal the truth about real scarcity:

- EU conventional meat production: 56 million tonnes (FAO 2023)

- EU organic meat production: 314,484 tonnes (0.6% of total) (European Commission 2019)

According to Mordor Intelligence, organic meat faces natural constraints that maintain its inelasticity:

- Preservation challenges without artificial additives

- Production costs that limit mass accessibility

- Growth rates tied to natural biology rather than industrial acceleration

These barriers explain why premium organic steaks command astronomical prices while factory-farmed meat floods supermarkets. The market clearly recognizes this qualitative difference, voting with its wallet for true quality despite limited supply.

When we examine what constituted “meat” historically versus today’s industrial output, the illusion of elasticity disappears. Authentic Vita assets remain as scarce as they’ve always been. We have simply changed how we measure and what we accept as valid units of account. The question isn’t whether we can produce more meat-like substances, but whether we can produce more real meat.

Self-Replication Revisited

Let’s return to Vita Money’s most fundamental property: self-replication. This isn’t simply about reproduction, it’s about maintaining quality across generations.

The difference between organic and conventional meat perfectly illustrates why this distinction matters. Scientific evidence proves these aren’t equivalent goods. A comprehensive study in the British Journal of Nutrition found that organic meat has:

- 23% higher levels of beneficial PUFAs

- 57% greater concentration of omega-3 fatty acids

- Enhanced mineral and antioxidant profiles

These nutritional advantages translate to real health benefits: from stronger heart health to better brain function. Organic meat isn’t just “different” meat, it’s fundamentally superior meat.

Such quality gap has profound monetary implications. You cannot measure true Vita inflation using substitute units with non-matching properties. Such distribution will come in handy later in the series when we dive deeper into GHOST analysis and its comparison to existing alternatives.

Great Monetary Reversal

Nature’s perfect money – the Vita standard that fed civilizations while expanding value – suffered history’s most puzzling monetary displacement. Consider the contradiction:

- Biological money with built-in scarcity

- Self-replicating value backed by nature

- Served as humanity’s original currency

- Time-tested across millennia

Yet despite these advantages, civilizations consistently abandoned Vita in favor of metal disks and paper. What forces could drive societies to replace a superior, time-tested monetary good with demonstrably inferior alternatives?