As of August 25, 2025, the combined market capitalization of cryptocurrency assets has reached nearly $4 trillion. Despite this monumental valuation, a clear, structured definition of Web3 remains surprisingly elusive.

In this article, we trace the origins and evolution of the terms Web1.0, Web2.0, and Web3.0 to establish a foundational understanding of what Web3 truly represents and why its definition matters.

Historical Context

It is important to note that the origins of Web 1.0, Web 2.0, and Web 3.0 are often shrouded in varying and sometimes conflicting narratives. To ensure accuracy, this analysis draws primarily from the academic paper “Understanding the Evolution of the Internet: Web 1.0 to Web3.0, Web3 and Web 3+” by Zheng and Lee (2023).

The following historical overview is intended to provide essential context for understanding the technological and philosophical shifts between each era of the internet, rather than to present an exhaustive or definitive account.

Web 1.0: The Read-Only Web

In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee, a researcher at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), invented the World Wide Web, what we now recognize as Web 1.0. This foundational version of the web functioned as a system of interlinked hypertext documents accessible over the internet. It is often called the “Read-Only Web” due to its minimal interactivity and static nature.

Websites during this era were largely informational, built from fixed content with little to no dynamic or interactive elements. User engagement was restricted to basic actions such as navigating through hyperlinks and sending text-based emails. The technology did not yet support features like image uploads, user comments, or real-time content updates, positioning Web 1.0 as a digital library rather than an interactive platform.

Web 2.0: The Read-Write Web

The term Web 2.0 was first introduced by information architect Darcy DiNucci in 1999. By the early 2000s, frustration had grown with the top-down, company-controlled nature of Web 1.0. Users began seeking more autonomy, not only to consume information but to create and share it themselves.

This shift gained formal recognition in 2004 when Tim O’Reilly hosted the first Web 2.0 Conference, cementing the term into public discourse. Web 2.0 marked the internet’s evolution into a Read-Write Web – a dynamic, participatory environment defined by user-generated content, social interaction, and enhanced usability.

This era saw the meteoric rise of social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, which empowered users to publish their own content and engage in real-time interaction. The parallel explosion of mobile technology – iPhones, Android devices, and the app economy – further accelerated this transformation. Applications like WhatsApp, Instagram, Uber, and Paytm turned smartphones into gateways for social and economic activity, embedding Web 2.0 deeply into daily life and solidifying a new model of the internet: centralized, interactive, and driven by platforms.

Web 3.0: The Semantic Web

Often referred to as the Semantic Web or the Read-Write-Execute Web, Web 3.0 represents a more intelligent, connected, and automated evolution of the internet. The concept was first introduced by the same Tim Berners-Lee, who envisioned a future in which machines could understand, interpret, and connect data across the web with minimal human intervention.

In this vision, the internet would transition from a collection of isolated information silos – where data on one platform remains separate from others – to an interconnected ecosystem of meaning. The goal of the Semantic Web is to enable machines to “understand” content contextually, allowing for smarter search results, automated services, and seamless data integration across applications and organizations. This effort is supported by standards developed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C).

Berners-Lee also imagined a more user-centric web. In a 2009 paper co-authored with Ching-man Au Yeung, he proposed decentralized social networks where users would retain control over their own data – storing it on trusted servers or devices, controlling privacy settings, and using universal identifiers (URIs) to manage their digital identities across apps.

However, this early vision of Web 3.0 faced significant practical challenges.

- It lacked a built-in incentive model to encourage adoption and participation

- Offered no native mechanism for transferring value, and

- Still relied on trusted third parties for data and value exchange.

As a result, it remained largely theoretical and was never widely embraced by the tech giants dominating the Web 2.0 landscape.

Web3: The Decentralized Web

Following the launch of Ethereum in 2014, co-founder Dr. Gavin Wood introduced a new, actionable vision for the next generation of the internet – Web3.

Responding to what he termed the “post-Snowden” era, Wood outlined four core pillars essential to this new decentralized web:

- A decentralized, encrypted system for publishing static content

- A messaging framework for transient or temporary information

- A trustless transaction layer enabled by consensus mechanisms

- An integrated user interface, including a native browser experience

This framework marked the first serious attempt to merge blockchain technology with the internet’s infrastructure, forming the basis of what the crypto industry now widely recognizes as Web3.

Although both Tim Berners-Lee and Gavin Wood shared a vision of a more user-centric and secure internet, their approaches diverged fundamentally. While Berners-Lee focused on semantic data and user-controlled storage through standards and protocols, Wood introduced cryptographic assurance and economic incentives via blockchain.

Web3 shifts control of personal data away from corporate intermediaries and back to users through decentralized storage, cryptographic key management, and self-sovereign identity. This user-centric model is operationalized through tools like cryptocurrency wallets (e.g., MetaMask), which allow individuals to manage their digital identities and control data access across applications without relying on central authorities.

Unlike logging into platforms via social media accounts – where users surrender their data – logging in with a crypto wallet ensures they retain ownership and granular control over their information. This embodies the core ethos of Web3: not just a smarter web, but a more sovereign one.

Summary

In our analysis, we will be focusing on the definition of Web3 as articulated by Dr. Gavin Wood. Web3 is a decentralized, user-centric internet built on cryptographic principles and blockchain technology. While the term Web 3.0 is sometimes used interchangeably with Web3, both point toward a future where the internet operates on open, trust-minimized protocols rather than corporate-controlled platforms.

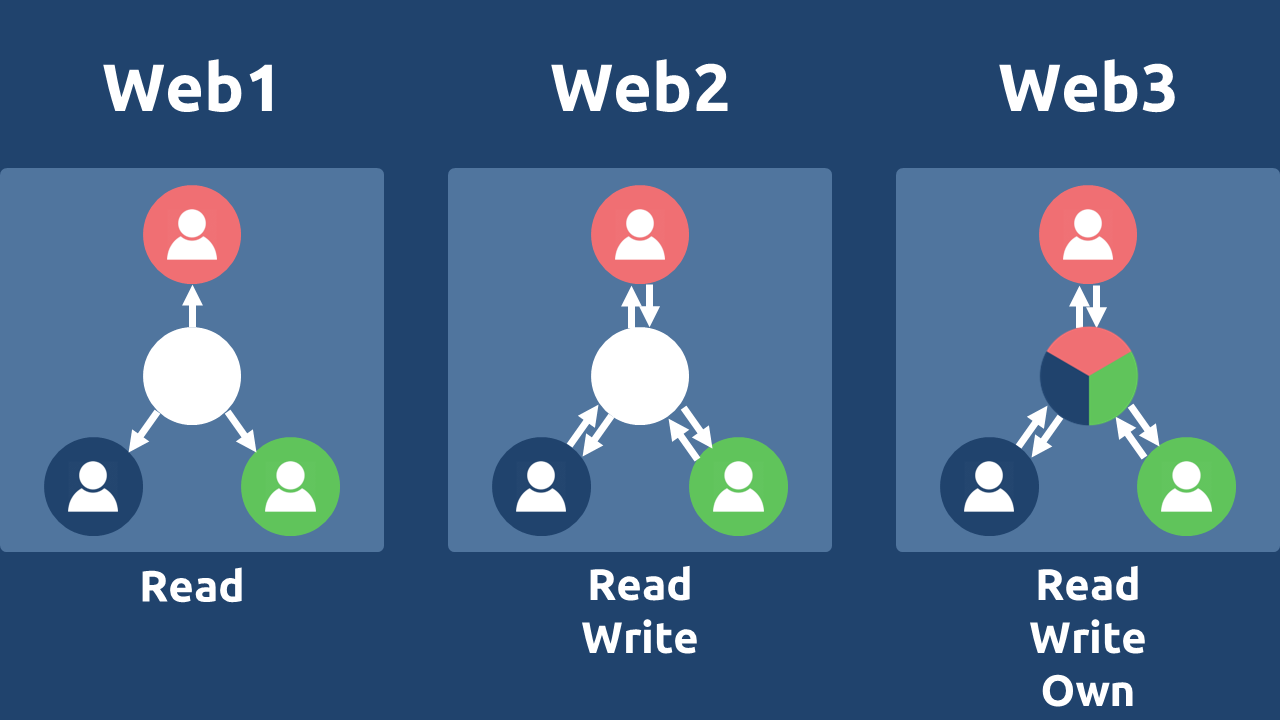

A common representation of the web’s evolution is captured in the popular framework shown in Figure 1, which categorizes Web1 as read-only, Web2 as read-write, and Web3 as read-write-own.

While useful at a high level, this framework falls short as a practical tool for classifying real-world projects. Clear-cut examples exist. Google is quintessential Web2, Bitcoin is pure Web3. But many innovations occupy a conceptual gray area. How would we categorize a platform like XRP, for instance?

This limitation reveals the need for a more nuanced and actionable framework. One that allows us to move beyond labels and evaluate projects based on their underlying architecture, incentives, and degree of decentralization.

That’s where we turn next. In the following article, we will move beyond broad labels and introduce a practical, inclusive evaluation framework designed to systematically assess where any project falls on the Web3 spectrum and what it truly means to build a decentralized future.

This new lens will help us better identify, compare, and champion the architectures that align with the principles of a truly open internet.