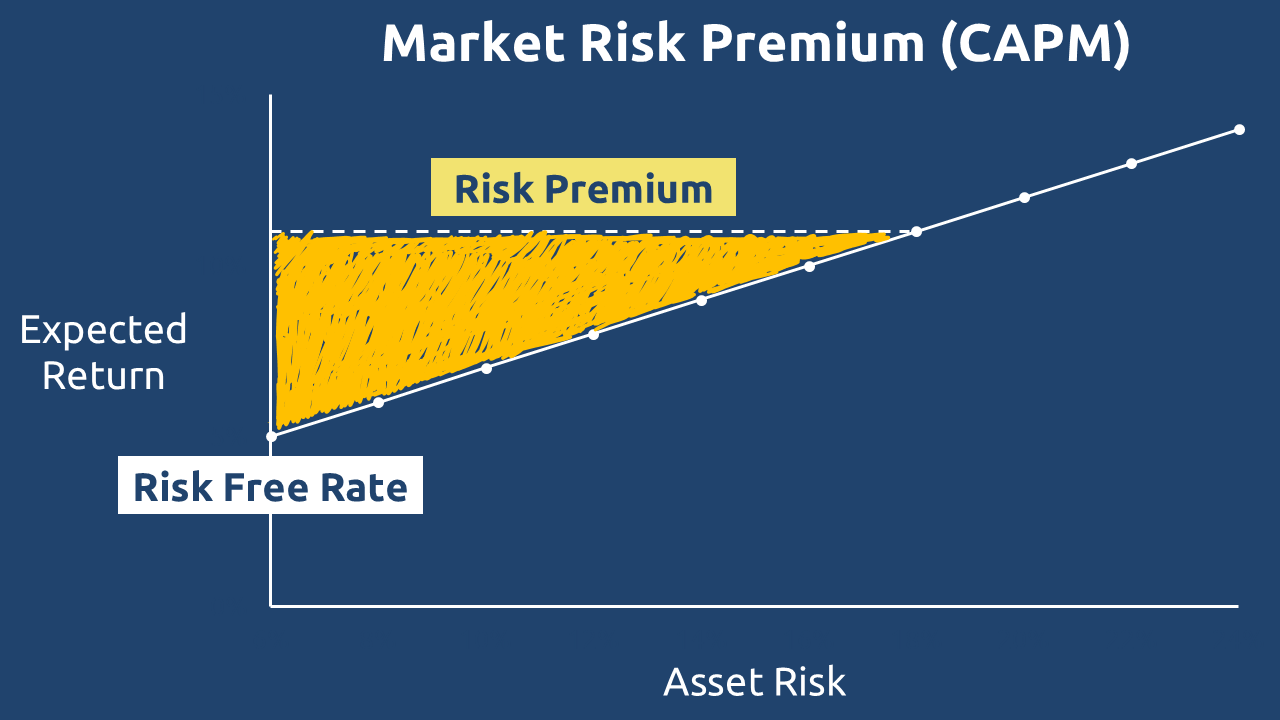

The Origins of Risk Premium

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), developed in the 1960s by William Sharpe and others, introduced a radical idea: an asset’s expected return could be mathematically derived from its risk premium – the additional reward investors demand for exposure to volatility beyond a “risk-free” baseline.

This theory emerged in a unique monetary era. The U.S. dollar was still gold-backed (via the Bretton Woods system, 1944 – 1971), granting Treasury bonds near-metallic credibility. The “risk-free asset” (typically the 10-year Treasury) was not just sovereign debt – it was de facto gold-proxy money, with:

- Scarcity: Dollar convertibility capped at $35/oz gold.

- Trust: The Fed’s balance sheet was anchored to physical reserves.

Thus, when CAPM declared Treasuries “risk-free,” it wasn’t mere abstraction – it reflected a world where the bond was as good as gold or at least, as good as a gold-pegged dollar could be.

The Post-Gold Standard Era

The year 1971 marked a monetary watershed – President Nixon severed the dollar’s gold convertibility, abandoning the last vestiges of the Bretton Woods system. This decision unfolded against a telling historical backdrop.

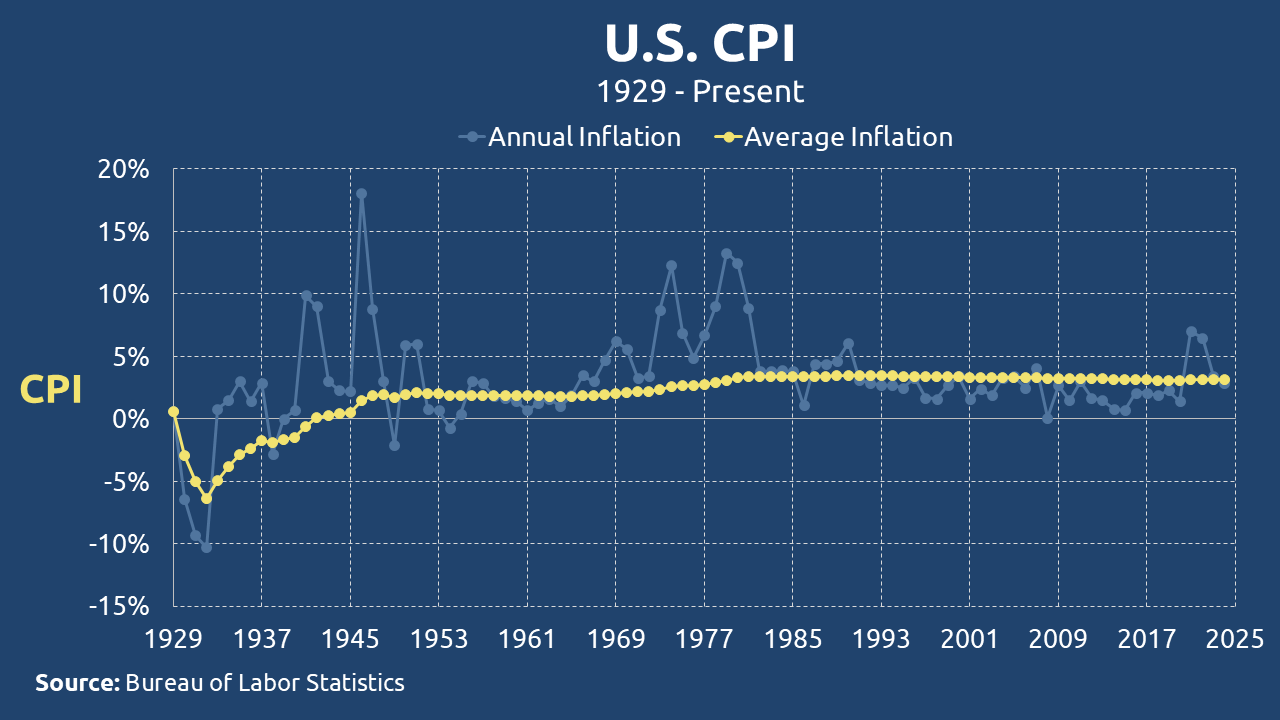

1929–1971 (Gold-Anchored Period):

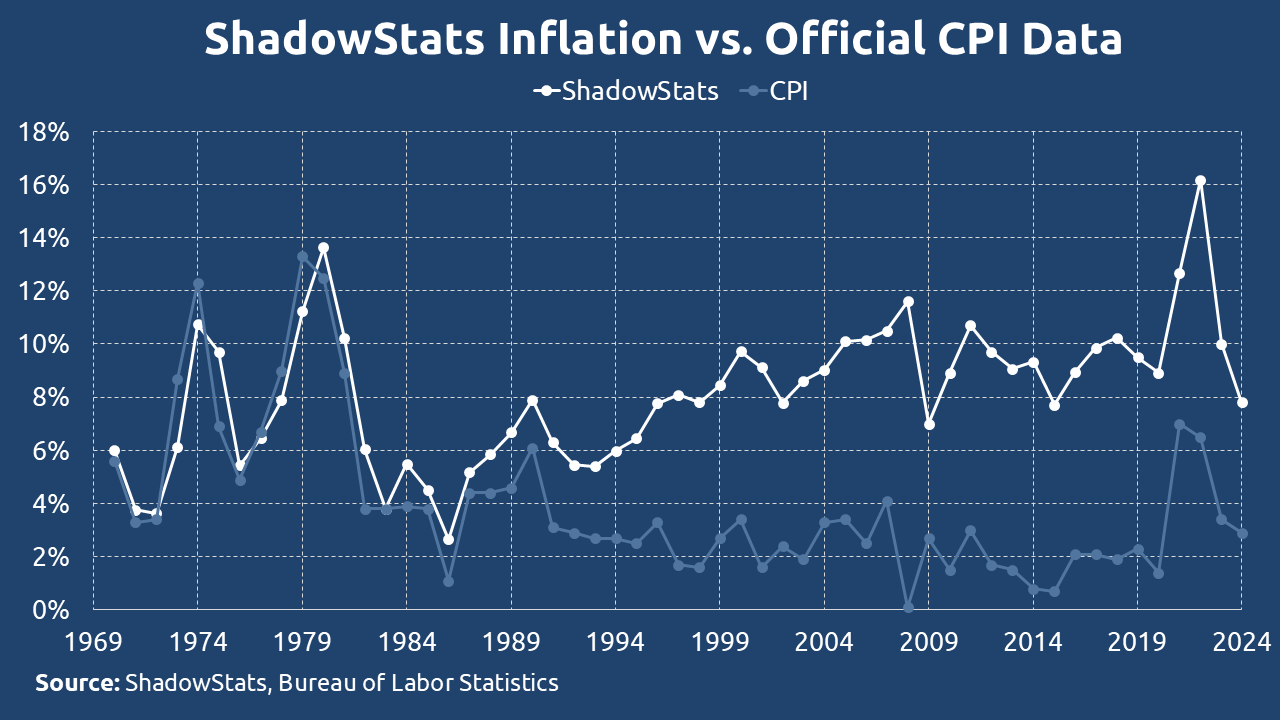

Despite catastrophic events – the Great Depression and World War II – the U.S. maintained remarkable price stability, with annualized inflation averaging just 1.96%. At this rate, the dollar lost half its purchasing power over 32 years.

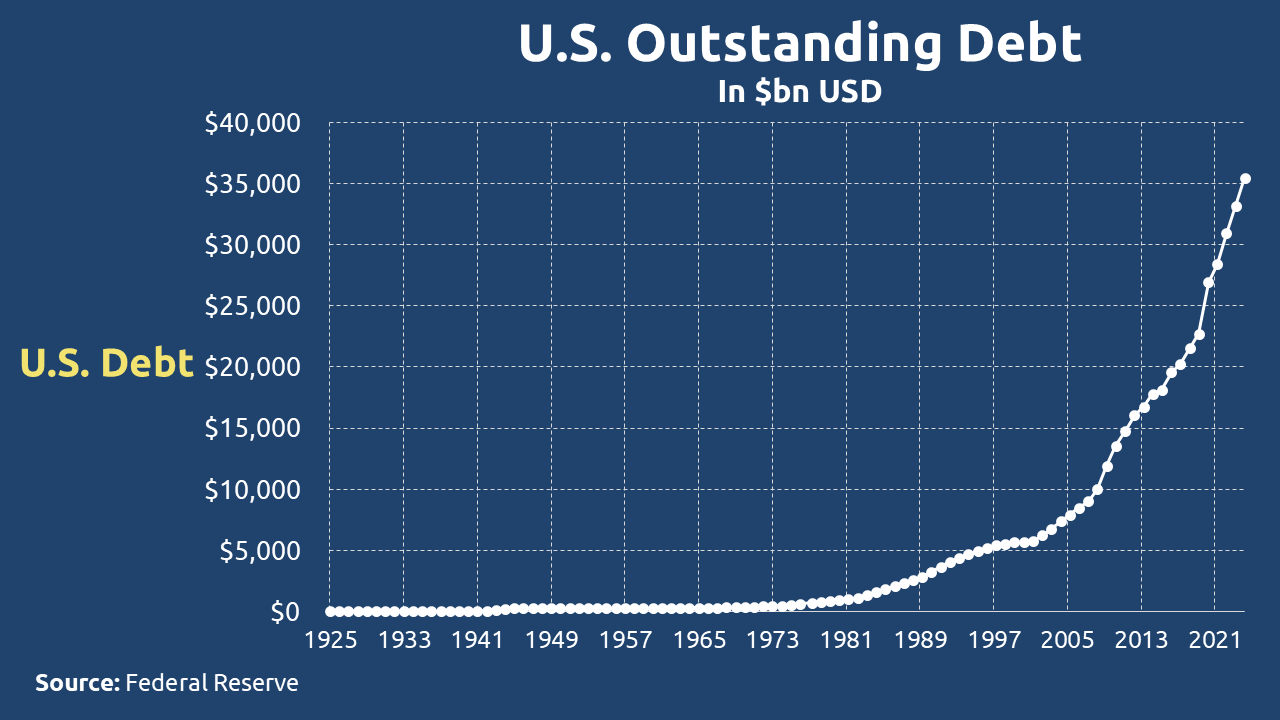

1971–2024 (Fiat Era):

Unleashed from gold’s discipline, inflation surged to 3.96% annually, accelerating the dollar’s decay. The same 50% devaluation now occurred in just 18 years – a 43% faster erosion of monetary value.

This inflationary acceleration coincided with a fundamental shift in what constituted “safe” assets. The CAPM framework, while revolutionary, assumed that U.S. Treasury bonds represented a truly risk-free benchmark.

At first glance, this seemed logical – the full faith and credit of the world’s largest capitalist economy stood behind these instruments. But the abolition of gold convertibility in 1971 replaced tangible backing with something far more abstract: trust in the U.S. government’s ability to manage its debt obligations.

The Trust Deficit

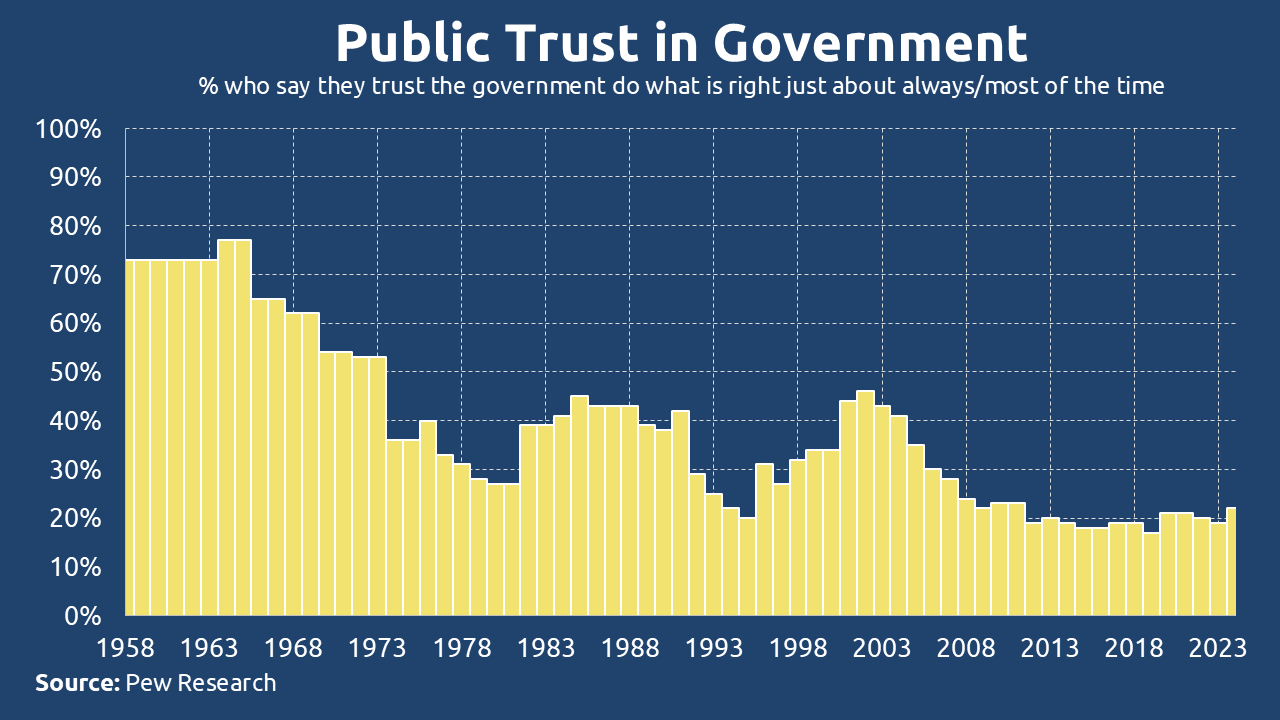

The trust deficit emerged immediately and grew steadily:

- Public confidence in government plummeted from 80% (1958) to 22% (2024) according to Pew Research

- This 75% decline in trust mirrors the dollar’s accelerated loss of purchasing power

- The “risk-free” asset became backed by political will rather than physical scarcity

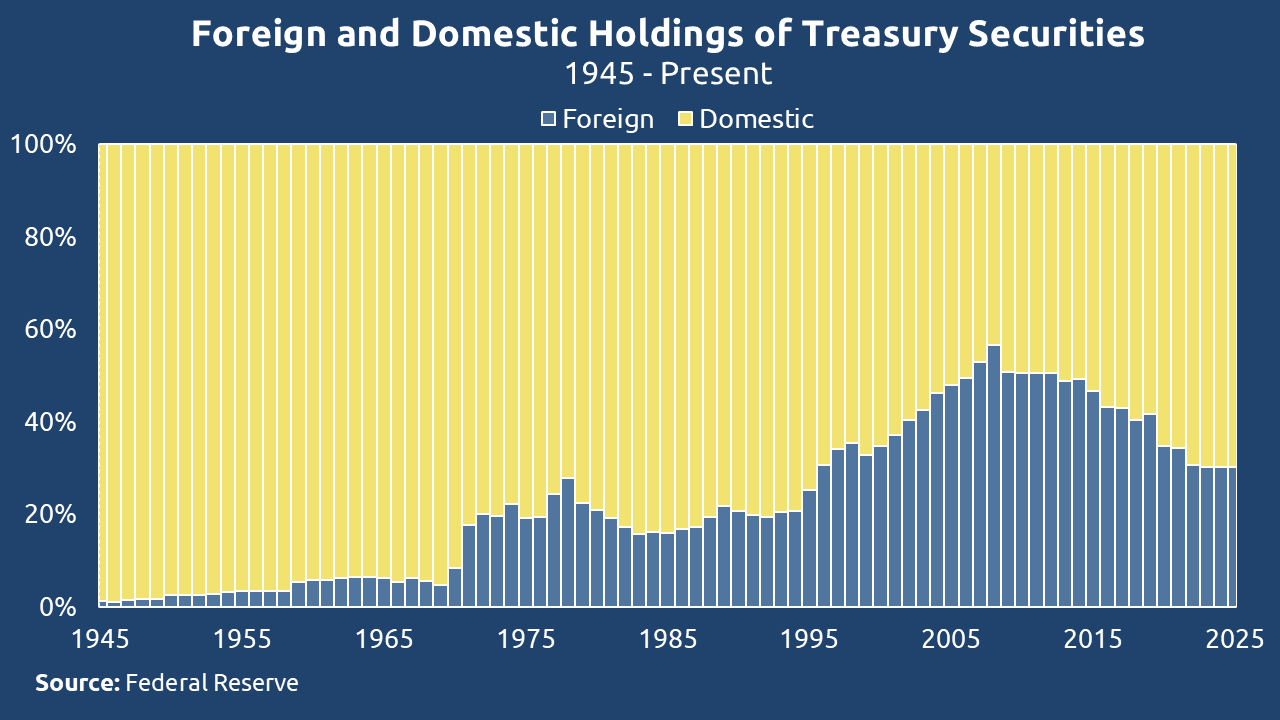

For decades after World War II, the United States leveraged its economic and geopolitical dominance to sustain demand for its debt – foreign central banks continued buying Treasuries, propped up by a combination of fear of dollar-dominated trade sanctions, respect for the world’s reserve currency, and control of the dollar hegemony in global finance.

However, the unchecked expansion of U.S. money supply and runaway fiscal deficits gradually undermined this dynamic. Foreign central banks began reducing their exposure:

- 2008: Foreign entities held 56% of U.S. debt

- 2024: That share has dwindled to just 30%

This 46% decline in foreign ownership signals a quiet but decisive shift – the world is losing confidence in the sustainability of U.S. monetary policy. The post-war “exorbitant privilege” of dollar dominance is fading, as nations increasingly question the long-term stability of a debt-backed fiat system.

With foreign central banks retreating, the burden of financing America’s debt explosion has shifted almost entirely to domestic financial players – a capitalist oligarchy propping up the system in exchange for power and privilege:

- Puppet Banks: Major banks, incentivized by Fed policies and backstopped by implicit bailout guarantees.

- Hedge Funds & Asset Managers: Speculators chasing yield in a distorted market, enabled by Fed liquidity injections.

- Pension Funds & Corporations: Captive buyers forced into Treasuries by regulation or short-term profit motives.

This is modern financial feudalism – a rigged game where the stick is the systemic risk (“everything collapse” if domestic institutions stop buying) and the carrot is the artificial yield premiums coupled with regulatory favors.

America occupied a privileged position in this monetary unraveling. Unlike other nations, the U.S. could export its debt burdens through a combination of trade dominance, military leverage, and financial capture of foreign elite capital. This exceptional arrangement allowed Washington to postpone its day of reckoning.

Yet the outcome remains universal. Across both privileged and ordinary economies, the same destructive pattern holds: reckless monetary expansion begets currency devaluation, which in turn destroys public confidence. The mechanisms differ, but all fiat systems ultimately confront the same erosion of trust.

Elasticity Premium

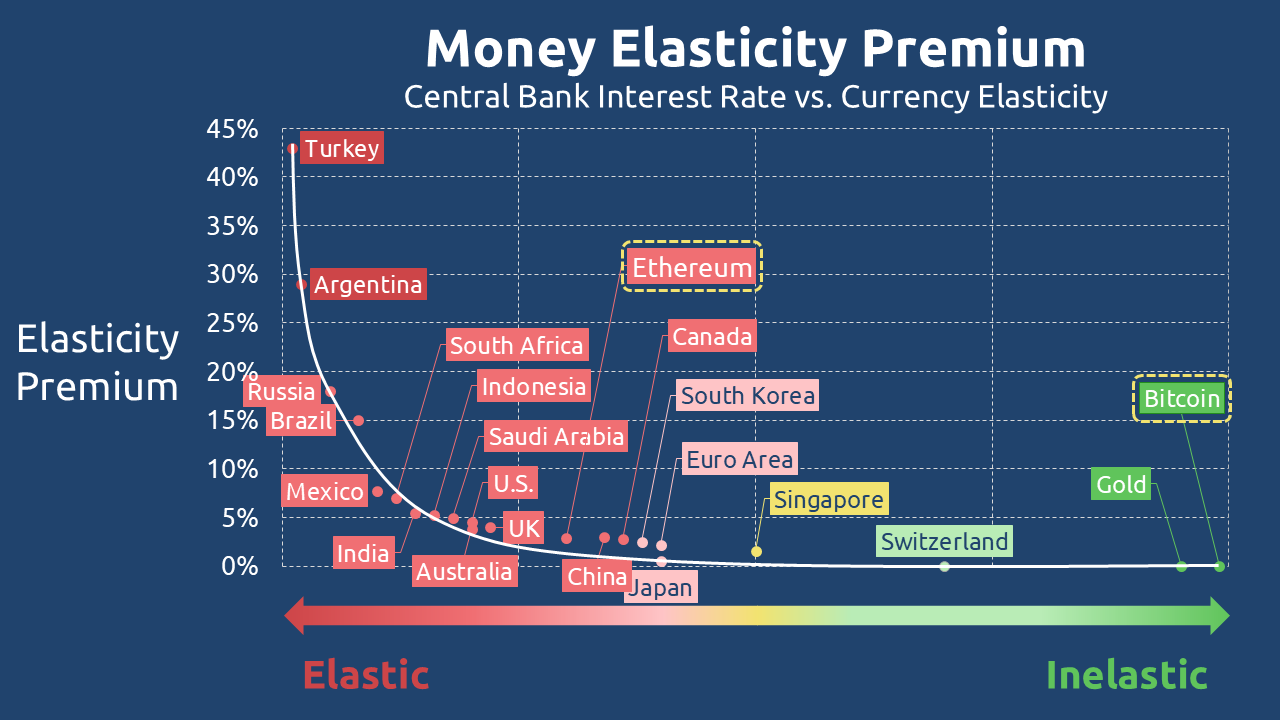

Here is a proposed framework for currency valuation. This new model ranks currencies according to their elasticity, where more elastic currencies would be required to pay a premium relative to their degree of elasticity. This premium would compensate holders for the higher volatility and inflation risks associated with elastic money supplies.

Since holding base currencies alone does not generate yield, government bonds – being short-term (inelastic) and long-term (elastic) instruments – serve as a mechanism to offset the underlying currency’s elasticity.

Further research is needed to refine the methodology for calculating currency elasticity, ensuring a standardized comparison matrix. This would involve assessing currencies both against each other and in relation to their respective money supply growth rates.

An intuitive allocation approach suggests that highly elastic currencies should command a higher premium to incentivize holding them, whereas inelastic currencies – being more stable – would warrant little to no premium. This differential pricing would reflect the inherent risks and stability of each currency.

The Elasticity Premium (Eₚ) is a yield-like dividend, denominated in the chosen currency, paid as compensation for holding that currency. It is calculated as:

Where:

- Eₚ = Expected Elasticity Premium

- ε = Elasticity of the currency

- γ = A coefficient reflecting macroeconomic factors such as debt levels, inflation, and monetary expansion

A highly inelastic currency (ε ≈ 0), such as gold or Bitcoin, would yield no Elasticity Premium:

This reflects their fixed or minimally expanding supply.

The Elasticity Premium is not merely a function of relative appreciation (e.g., gold rising in USD terms). Instead, it represents an explicit increase in the quantity of the currency held, serving as direct compensation for its elasticity risk.

Reimagining Money: Do We Have the System We Deserve?

The current monetary system operates on elastic currencies – money that can be inflated, devalued, and manipulated. But is this truly the best we can do?

What if we had sound, inelastic money – money with a fixed or predictable supply – that not only preserved its value but also paid a premium? And what if that premium itself were denominated in equally inelastic money, ensuring its value couldn’t be diluted?

Imagine a world where holding money didn’t mean slowly losing purchasing power, but instead meant earning real, non-depreciating yield. That’s the future we should strive for – a system where money is stable, scarce, and rewarding for those who hold it.

Is such a system possible? It’s not just a fantasy – it is a challenge to rethink the very foundations of our monetary architecture.

[1] The inflation statistics referenced here were compiled through independent analysis of ShadowStats’ published materials. This presentation does not constitute an authorized reproduction of ShadowStats’ proprietary data, nor does it imply endorsement by ShadowStats. The figures were manually derived from publicly available sources.